A Midsummer Night’s Dream

“The course of true love never did run smooth.”

About the work

2013

Welcome to the Michael Grandage Company’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare

Lysander loves Hermia. Hermia loves Lysander. Helena loves Demetrius. Demetrius used to love Helena but now loves Hermia. In the surrounding forest Oberon and Titania, the King and Queen of the Fairies, are having their own battle of love. As the human and magical worlds collide, mischief and chaos erupt, and love at first sight proves a reality for some but makes an ass of others.

Sheridan Smith plays Titania and David Walliams plays Bottom in this new production of one of Shakespeare’s greatest comedies.

“Here I was looking for a popular play in the season to answer conversations I was having with particular actors. I met David Walliams – who astonished me by bringing a very long list of plays that interested him. One was A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I’d also met Sheridan Smith separately and she’d talked about developing her career as an actor – and out of those conversations came the programming of a great popular classic play.

I once directed it in Sheffield in an amazingly short run and didn’t really explore it as well as I’d like to have done. I’m coming at it from a completely different angle this time, but also seeking something that is a bit populist. The casting fulfils a wonderful brief for us which is to get Shakespeare to the kind of people we hope will be really turned on by it.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

Theseus, Duke of Athens, is busy with preparations for his wedding to Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons. The excited Athenian people organise parties and entertainment, including a group of local craftsmen turned amateur actors, led by Peter Quince and Nick Bottom, who plan to perform a play in honour of the occasion. But before he can enjoy the festivities, Theseus has to deal with Egeus, an aging nobleman who’s come to his court demanding justice.

Egeus wants his daughter, Hermia, to marry Demetrius, but she refuses, claiming to love his rival Lysander instead. The nobleman insists the Duke instruct Hermia to do her duty as a daughter, or otherwise risk the penalty of ancient Athenian law – the death sentence. A reluctant Theseus gives Hermia until his own wedding day to make a decision, reminding her that she should obey her father in all things.

Desperate, Hermia and Lysander decide to run away the next night to a relative of Lysander’s, many miles from Athens, where they can be safely married. They tell Hermia’s childhood friend, Helena, of their plans. But Helena has her own reasons for not keeping their secret… She’s smitten with Demetrius, to whom she was once engaged until he rejected her for Hermia. If she tells him about Hermia and Lysander’s plans to elope maybe he’ll like her again? Demetrius chases after the fleeing lovers, who disappear into the nearby woods, with Helena in pursuit.

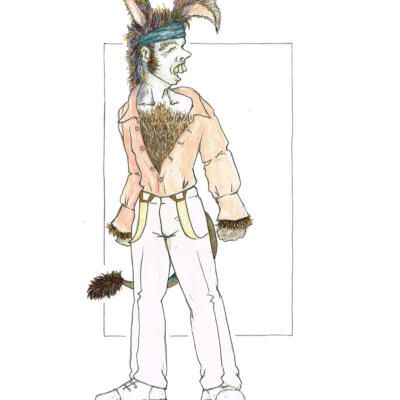

The woods are a strange place, though, ruled over by Oberon, King of the Fairies. He and his Queen, Titania, have recently argued and now Oberon plans to punish her with a spell. He instructs his jester, Puck, to find a magic flower which, when sprinkled on the eyelids of a sleeping man or woman, will make them fall instantly in love with the first thing they see. Unfortunately for Titania that’s unsuspecting Nick Bottom, who – during rehearsals in the woods – has been transformed by a mischievous Puck into a donkey.

Having observed Demetrius’ mistreatment of Helena, Oberon also orders Puck to sprinkle the magic flower on the young man’s eyes, so that he’ll fall back in love with his jilted fiance. All goes to plan until Puck mistakes Lysander – lying asleep in the woods with Hermia – for Demetrius, performs the spell, whereupon Lysander falls instantly in love with Helena, who finds and wakes him anxious that he’s injured or dead.

In trying to correct his mistake, Puck puts a spell on Demetrius – who switches his affections back to Helena – leaving the young woman confused and upset by the advances of the two apparently mocking young noblemen. When Hermia wakes to discover she’s been abandoned, she turns on her old friend Helena, accusing her of betrayal.

Witnessing all this, Oberon tells Puck to make amends or risk his wrath, plus the everlasting unhappiness of the four young lovers and the ruin of Theseus’ wedding day. The wayward fairy has until sunrise to put things right…

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

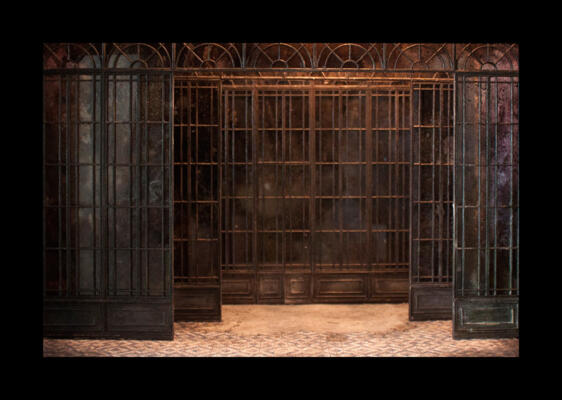

| Director | Michael Grandage |

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Lighting Designer | Paule Constable |

| Composers & Sound Designers | Ben & Max Ringham |

| Casting Director | Anne McNulty |

| Movement Director | Ben Wright |

| Wig & Hair Designer | Richard Mawbey |

| Production Manager | Paul Handley |

| Company Stage Manager | Sophie Gabszewicz |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Lorna Earl |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Oliver Bagwell Purefoy |

| Voice & Dialect Coach | Penny Dyer |

| Music Coach | Nigel Lilley |

| Props Supervisor | Celia Strainge |

| Costume Supervisor | Poppy Hall |

| Head of Wardrobe | Tim Gradwell |

| Head of Wigs & Make-Up | Gemma Flaherty |

| Deputy Head of Wardrobe | Charlotte Stidwell |

| Wardrobe Assistant | Rachael McIntyre |

| Associate Director | Tara Robinson |

| Associate Set & Costume Designer | Lee Newby |

| Associate Lighting Designer | Rob Casey |

| Associate Sound Designer | Joel Price |

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was born in April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon and educated at the town’s grammar school. He had been working as playwright and actor in London’s playhouses for some five years by the mid-1590s, when A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written and performed, and had published two narrative poems, The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis. His Sonnets, privately circulated and dating from 1593 and 1603, were first printed in 1608. A series of romantic comedies were performed between 1597 and 1601: The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado about Nothing, As You Like It and Twelfth Night. These years also saw the two parts of King Henry IV, King Henry V, King John and Julius Caesar, and Hamlet, thought to date from around 1600. Between 1602 and 1606 came a number of plays that were barely comedies but not clearly tragedies: Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure and All’s Well That Ends Well. From the same period are the great tragedies: Othello, King Lear, Hamlet, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. In later years he favoured stories with a freer, romantic range, the last of these being The Tempest (1610-11). His last known dramatic works were written in collaboration with John Fletcher: The Two Noble Kinsmen and All Is True (also known as King Henry VIII), performed in 1613. After retiring to Stratford-upon-Avon Shakespeare died there on 23 April 1616.

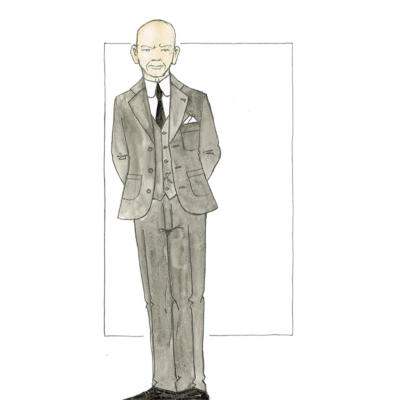

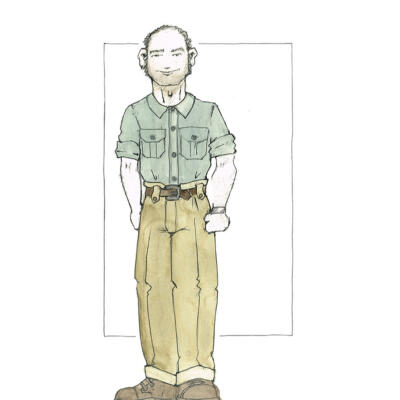

Theseus & Oberon (Padraic Delaney)

Theseus, Duke of Athens, and Oberon, King of the Fairies

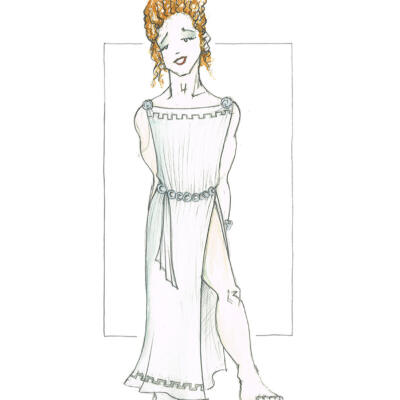

Hippolyta and Titania (Sheridan Smith)

Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, betrothed to Theseus, and Titania, Queen of the Fairies

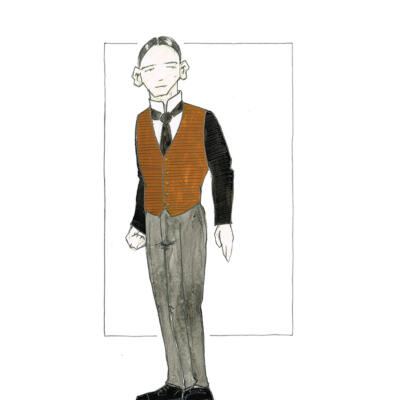

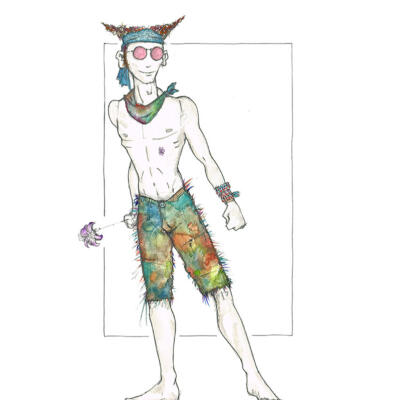

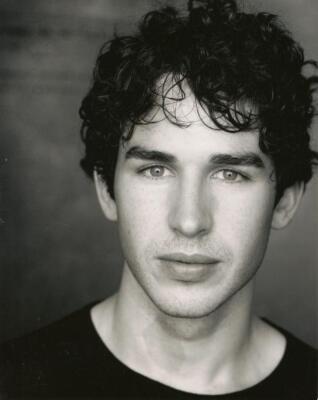

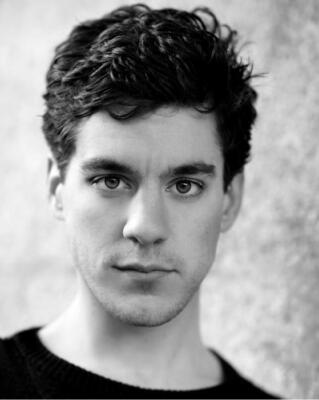

Philostrate and Puck (Gavin Fowler)

Philostrate, Theseus’ Master of the Revels

and Puck/Robin Goodfellow, Oberon’s jester and lieutenant

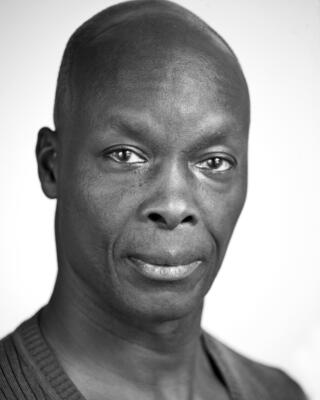

Egeus (Leo Wringer)

Hermia’s father

Lord and Fairy (Jack Brown)

Attending on Theseus and Hippolyta

and also on Oberon and Titania

Hermia (Susannah Fielding)

Daughter to Egeus, in love with Lysander

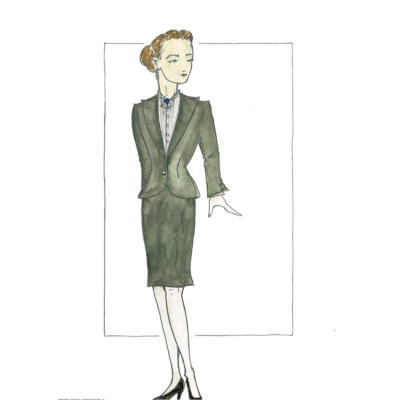

Helena (Katherine Kinglsey)

In love with Demetrius

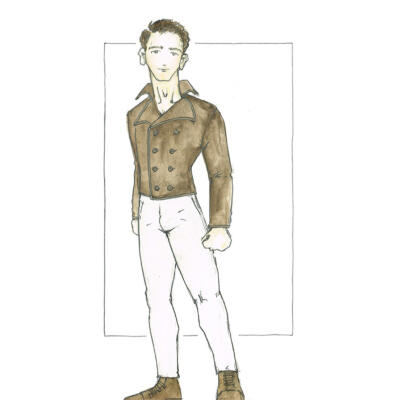

Lysander (Sam Swainsbury)

In love with Hermia

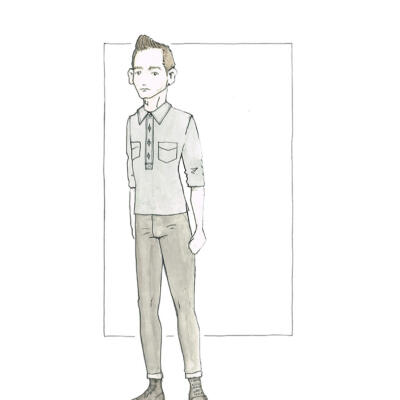

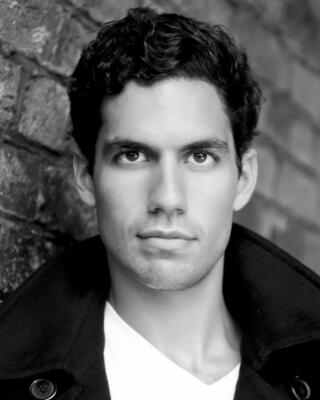

Demetrius (Stefano Braschi)

In love with Hermia

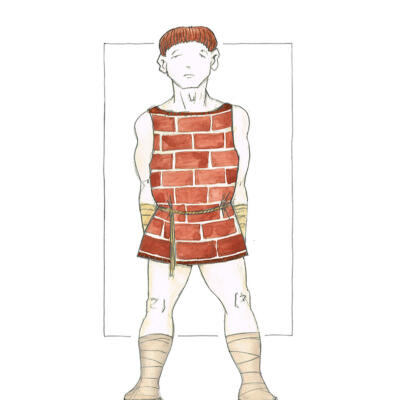

Peaseblossom and Tom Snout (Henry Everett)

Peaseblossom, a fairy in Titania’s service, and Tom Snoutt, a tinker playing Wall in the Interlude

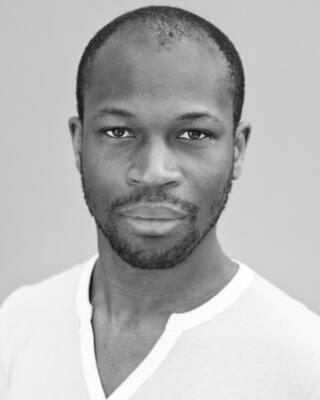

Cobweb and Robin Starveling (Stefan Adegbola)

Cobweb, a fairy in Titania’s service, and Robin Starveling, a tailor playing Moonshine in the Interlude

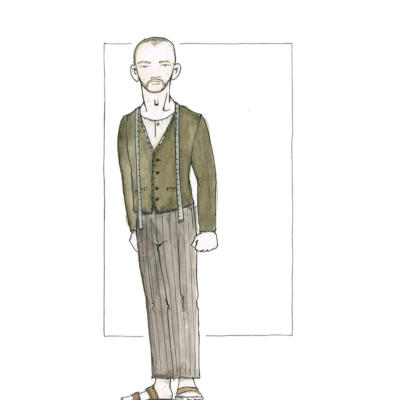

Moth and Peter Quince (Richard Dempsey)

Moth, a fairy in Titania’s service, and Peter Quince, a carpenter playing Prologue in the Interlude

Mustardseed and Francis Flute (Alex Large)

Mustardseed, a fairy in Titania’s service and Francis Flute, a carpenter playing Thisbe in the Interlude

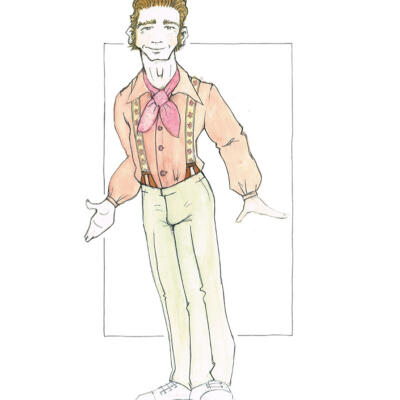

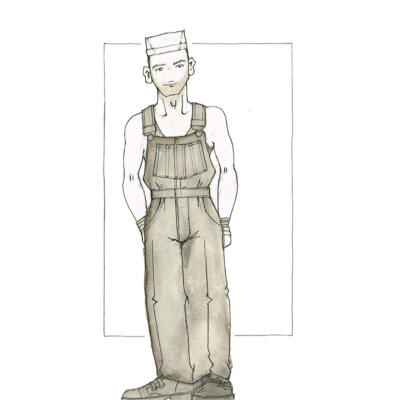

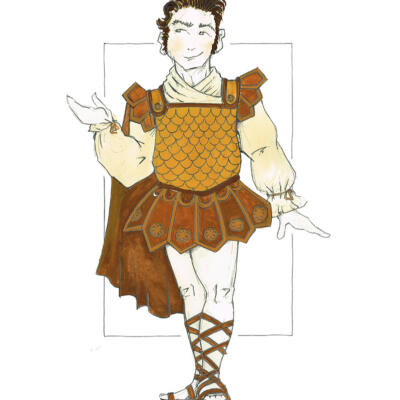

Nick Bottom (David Walliams)

Nick Botton, a weaver playing Pyramus in the Interlude

Snug (Craig Vie)

Snug, a joiner playing Lion in the Interlude

“Gentles, perchance you wonder at this show…”

By Russell Jackson

A Midsummer Night’s Dream has a generosity of spirit, a lyricism and lightness of touch and a delight in its own devices that have entertained audiences royally for more than 400 years. It gives us a privileged view of parallel realms of existence, and of the great medium it celebrates: the theatre. There are mortal characters with the glamour of a mythological past; supernatural beings with all-too-human problems of their own; and working men who attempt a classical tragedy of love and end up delivering comedy as sublime as that of Laurel and Hardy’s endearing incompetence. Each realm has its own order and decorum, but none fully apprehends the existence of the others. Because these are all contained in that other world of the playhouse, the play achieves ‘the concord of this discord’. Beyond these worlds and that of us, the playgoers, are the elements, the moon, and the cosmos. Disorder leads to a new order or – as Puck puts it in more homely terms – ‘The man shall have his mare again, and all shall be well.’

The play was first published in 1600, but has been thought to date from 1594-96, around the time of Romeo and Juliet and Richard II. It has often been suggested that it was written for an aristocratic wedding at a great country house, but there is no conclusive evidence for this. Shakespeare’s Dream evokes a magical time of year and a ‘magic hour’ or two in the freedom of the woods. Theseus, who has won the heart of the Amazonian queen he recently conquered in battle, makes the all-important point in the play’s first lines, connecting the passage of time, the Moon and the urgency of desire:

“…four happy days bring in

Another moon – but O, methinks, how slow

This old moon wanes! She lingers my desires”

After this, references to the moon recur. Theseus feels obliged to enforce the ‘harsh Athenian law’ that would condemn Hermia to death or to life as a nun (‘chanting faint hymns to the cold fruitless moon’) if she does not consent to marry Demetrius, the suitor favoured by her father. Lysander proposes escape from Athens, and Hermia suggests a more romantic view of moonlight, better suited to lovers’ needs:

“Tomorrow night, when Phoebe doth behold

Her silver visage in the wat’ry glass,

Decking with liquid pearl the bladed grass

(A time that lovers’ flights doth still conceal)

Through Athens’ gates have we devis’d to steal.”

Helena, still carrying a torch for Demetrius, despite his wooing of her friend, reflects that

“Things base and vile, holding no quantity,

Love can transpose to form and dignity.

Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind,

And therefore is wing’d Cupid painted blind.”

But there are other forces at work that no-one has reckoned with so far…

Athenian workmen are preparing a play that they hope will be performed as part of the wedding festivities. Pyramus and Thisbe, to avoid the opposition of their parents to their union, will plan to meet by moonlight, will fatally miss each other and – separately – commit suicide. The anxious discussion of the means of achieving illusion puts the deceptive magic of theatre at the centre of the comedy’s agenda. Rehearsing in the woods seems the best way of avoiding their planned effects (‘devices’) being known. All the mortals who head for the forest are about to encounter a regime whose transformative powers and its own ‘devices’ go beyond even love or the theatre.

Transforming things ‘base and vile’ to ‘form and dignity’ and (more interestingly) vice versa are the business of the woodland folk, and in their realm the potential consequences are more serious. There is a power struggle, and Oberon, angered by Titania’s refusal to give him her ‘Indian boy’, puts her under a spell that will make her fall in love with the first creature she sees when she wakes from her sleep. The wild card is Puck, a mischief-maker who provides the amusement for the fairy king that the workmen’s play will offer to Theseus and Hippolyta. Puck turns Bottom into an ass, sexually potent but hardly appropriate as bedfellow for the fairy queen.

Titania invokes another attribute of the moon when she wakes and immediately falls in love with Bottom and commands her fairies to ‘lead him to my bower.’

“The moon, methinks, looks with a watery eye,

And when she weeps, weeps every little flower,

Lamenting some enforcèd chastity.

Tie up my love’s tongue; bring him silently.”

Bottom is about to enjoy (and, poor ass, forget) a sexual experience more intense than the kind that the mortal lovers are careful to avoid. He will emerge from his dream – the only way he can make sense of his night in the forest – with a vague though pleasing sense of what has occurred. Titania’s lyrical force is both touchingly direct and sophisticated:

“So doth the woodbine the sweet honeysuckle

Gently entwist; the female ivy so

Enrings the barky fingers of the elm.

O, how I love thee! How I dote on thee!”

Not only is she a spirit of another rate, she knows her plant life.

In the final act the discrete worlds of the play frame each other in turn, with Theseus announcing that he ‘never may believe / these antique fables, nor these fairy toys’ and Hippolyta replying that ‘all the story of the night told over…grows to something of great constancy.’ The play of Pyramus and Thisbe, ‘very tragical mirth,’ transforms a legendary tragedy into a comedy that, in its own way – not understood by the actors or their on-stage audience – is a commentary on the follies of the night; and the fairies’ arrival to bless the ‘bride-bed’ and the house, with Puck brushing the dust behind the door, brings human domestic reality and supernatural powers together. The last moments turn towards the audience, and one of the ‘shadows’ that have been both actors and rulers of the fairy world speak directly to us – without the mortals knowing it. We have a secret we share with the fairies.

Russell Jackson is Allardyce Nicoll Professor of Drama at the University of Birmingham. His most recent publications include Shakespeare Films in the Making (2007) and Theatres on Film: How the Cinema Imagines the Stage (2013).

A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (Michael Grandage Company, Ltd., 2013) – the text of MGC’s 2013 production of the play at the Noel Coward Theatre. Many other editions, with introductions and commentaries, are available.

The following books were in the rehearsal room for A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

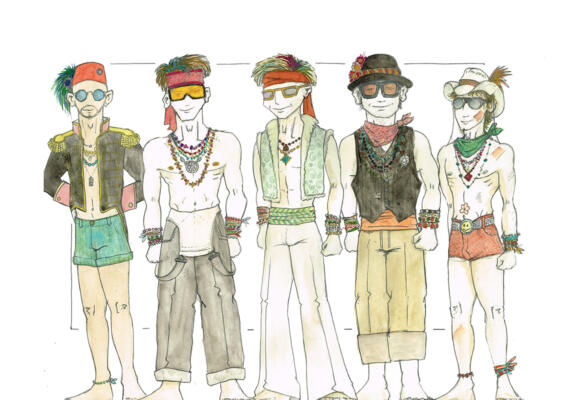

- Burning Man – Art in the Desert – A. Leo Nash (Abrams)

- Desert to Dream – A Dozen Years of Burning Man Photography – Barbara Traub (Immedium)

- The Woods – David Vance (Pohlmann Press)

- Portrait of a Generation – The Love Parade Family Book – Alfred Steffen (Taschen)

- Deborah Turbeville (Congreve)

- Deborah Turbeville – Past Imperfect 1978-1997 (Steidl)

- Deborah Turbeville – The Fashion Pictures (Rizzoli)

- All of a Sudden – Jack Pierson