Hughie

About the work

2016

Welcome to Michael Grandage Company’s production of Hughie by Eugene O’Neill

1928, New York City. A hotel lobby.

A small-time gambler and big-time drinker makes his way back to Room 492. With a new night clerk on duty, he is forced to confront his personal demons and discover the real end to his own story.

Hughie is a rarely seen theatrical masterpiece about the loneliness and redemption of one man chasing the American Dream.

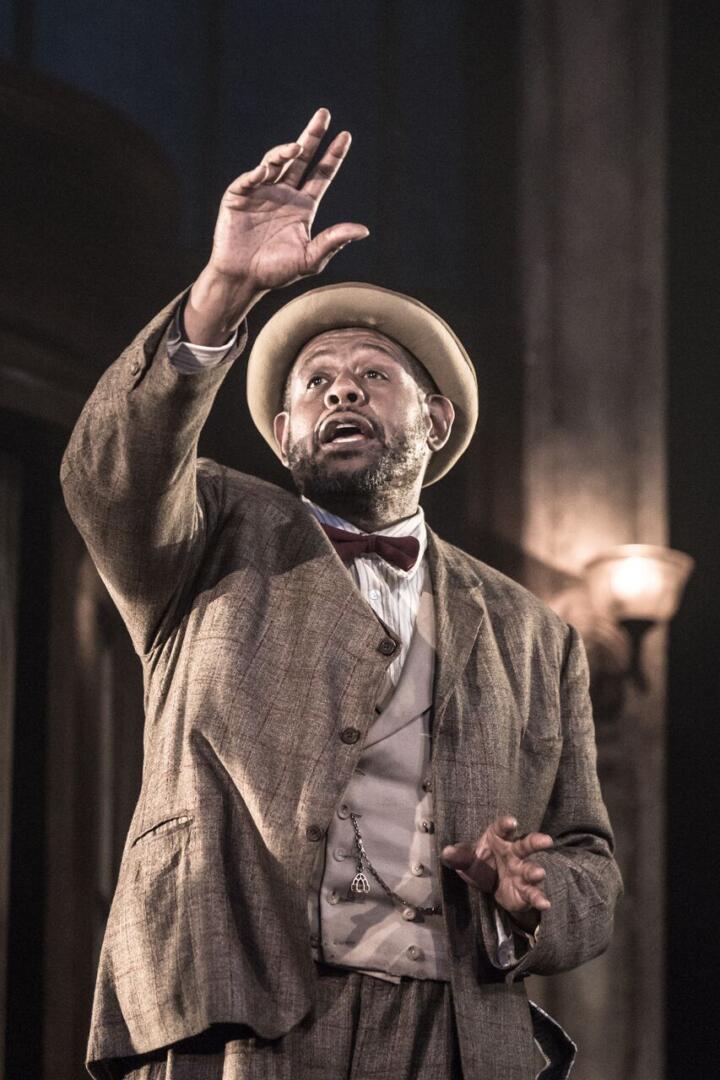

Michael Grandage directs Academy Award, Golden Globe Award and BAFTA winner Forest Whitaker and Tony Award winner Frank Wood in this Broadway revival by one of America’s greatest playwrights.

“Great drama addresses the human condition in a profound way and at the same time has the ability to speak to us individually. As one of America’s greatest dramatists, Eugene O’Neill consistently tackles important topics such as loneliness, addiction, grief, disillusionment and the search for the American Dream in a way that reaches us on a very personal level and makes us reflect upon our own lives.

Such is the case in Hughie. O’Neill masterfully excavates a panoply of these big ideas into a succinct hour-long evening of theatre. It is a play about the need for connection, and how through such connection one can find redemption.

I am thrilled to be directing this rare revival with two extraordinary talents. Forest Whitaker is a towering actor with a remarkable ability to define character. To be working with him to tell the story of Hughie is not only an incredible opportunity but also a privilege. I feel equally inspired by Frank Wood, a celebrated Broadway veteran, who through his carefully crafted silence speaks volumes about O’Neill’s themes of desolation and hopelessness.

Now, more than seventy years after O’Neill put pen to paper, the themes in Hughie resonate louder than ever – especially our desire to stay connected to others. I cannot think of a better way to connect than through the shared experience of theatre. I hope you will enjoy studying this rare gem and exploring the inner lives of these two dynamic characters.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

The early hours of the morning, summer 1928. A hotel lobby in New York City.

Just steps beyond the bright lights of Broadway, Erie Smith, a small-time gambler and big-time drinker, returns to the faded hotel that he has made his home. There he encounters the new night clerk, Charlie Hughes, and laments how his luck has gone bad since the death of Hughie, Charlie’s predecessor.

As the early hours of the morning give way to yet another dawn, Erie continues to tell tall tales, searching for the American Dream in order to survive.

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

| Director | Michael Grandage |

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

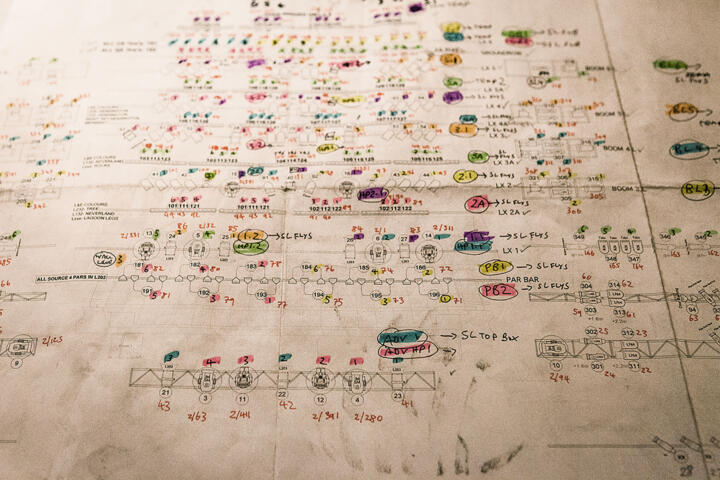

| Lighting Designer | Neil Austin |

| Composer & Sound Designer | Adam Cork |

| General Management | 101 Productions |

| Company Manager | Lizbeth Cone |

| General Press Representative | Polk & Co. |

| Casting | Calleri Casting |

| Production Management | Aurora Productions |

| Production Properties Supervisor | Buist Bickley |

| Production Stage Manager | Peter Wolf |

| Stage Manager | Lisa Buxbaum |

| Technical Supervisor | Ben Heller |

| Associate Director | Timothy Koch |

| Associate Set Designer (UK) | Lee Newby |

| Associate Set Designer (US) | Daniel Muller |

| Scenic Associate | Frankie Bradshaw |

| Associate Costume Designer | Amanda Seymour |

| Associate Lighting Designer | Gina Scherr |

| Associate Sound Designer | Christopher Cronin |

| Wardrobe Supervisor | Eileen Miller |

| Vocal Coach | Kate Wilson |

| Movement Coach | Taaj Jaharah |

| Production Assistant | Megan Sprowls |

| Behind the Scenes Guide | Rachel Weinstein & Tim Koch |

| Behind the Scenes Editor | Dominic Francis |

Eugene O’Neill

Eugene O’Neill was born on 16th October 1888 in New York City – in the Barrett House, a hotel on Broadway and 43rd Street similar to the one in which Hughie is set. The son of famous Irish actor, James O’Neill, he was raised in the theatre and would later come to be regarded as the first great American playwright.

Eschewing the popular vaudeville and melodrama of the day, as typified by his father’s generation, O’Neill wrote plays that drew directly from his own life and experiences, inspired by such celebrated European writers as Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg and Anton Chekhov. A prolific author, he ultimately won a total of four Pulitzer Prizes for his work and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936 – the only American playwright ever to have won the award.

O’Neill’s major plays include: Beyond the Horizon (1918 – Pulitzer Prize 1920), Anna Christie (1920 – Pulitzer Prize 1922), The Emperor Jones (1920), The Hairy Ape (1922), All God’s Chillun Got Wings (1924), Desire Under the Elms (1924), The Great God Brown (1926), Strange Interlude (1928 – Pulitzer Prize), Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Ah, Wilderness! (1933) and A Moon for the Misbegotten (written 1941-1943, first performed 1947). Many regard The Iceman Cometh, written in 1939 and first performed in 1946, and Long Day’s Journey Into Night as his greatest work. The latter was written in 1941 and first performed in 1956, three years after the author’s death, for which he was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1957.

After a lifetime of recurring depression and alcoholism, O’Neill eventually died of a neurological disorder aged 65 on 27th November 1953 in Boston – in the Sheraton Hotel on Bay State Road. His last reported words were allegedly: ‘I knew it… Born in a hotel room and died in a hotel room.’

Eugene O’Neill’s use of stage-directions

Some scholars believe that Eugene O’Neill never intended for Hughie to be performed, but rather to be read as a work of literature. As such, the stage-directions are equally as important as the dialogue he puts into the mouths of his characters, underscoring the themes of loneliness and desolation through figurative language, metaphor and symbolism.

In his directions, O’Neill uses vivid imagery to give voice to the Night Clerk’s inner-thoughts and memories in a way that could not be conveyed through spoken dialogue. He seems to wrap the past, present and future into one inseparable knot that defines the feeling of absence and longing often found in human existence.

Elaborate stage-directions became a trend among playwrights in the early twentieth century. Celebrated British dramatists, such as George Bernard Shaw and Harley Granville Barker, used extensive directions to convey intentions and to offer psychological and sociological explanations for their characters’ behaviour.

In performance, they function as an aid to help the actor develop the inner-life of a character. In Hughie the stage-directions establish the disconnection between Erie and the Night Clerk.

Erie Smith (Forest Whitaker)

‘A teller of tales.’ Early 40s.

In manner, he is consciously a Broadway sport and a Wise Guy – the type of small fry gambler and horse player, living hand to mouth on the fringe of the rackets. Infesting corners, doorways, cheap restaurants, the bars of minor speakeasies, he and his kind imagine they are in the Real Know, cynical oracles of the One True Grapevine.

Erie usually speaks in a low, guarded tone, his droop-lidded eyes suspiciously wary of nonexistent eavesdroppers. His face is set in the prescribed pattern of gambler’s dead pan. His small, pursy mouth is always crooked in the cynical leer of one who possesses superior, inside information, and his shifty once-over glances never miss the price tags he detects on everything and everybody. Yet there is something phoney about his characterization of himself, some sentimental softness behind it which doesn’t belong in the hard-boiled picture.

A Night Clerk (Frank Wood)

Tall, thin, with a scrawny neck and jutting Adam’s apple. His face is long and narrow, greasy with perspiration, sallow, studded with pimples from ingrowing hairs. His nose is large and without character. So is his mouth. So are his ears. So is his thinning brown hair, powdered with dandruff. Behind horn-rimmed spectacles, his blank brown eyes contain no discernible expression. One would say they had even forgotten how it feels to be bored.

The play and past productions

Hughie was written between 1941 and 1942, shortly after Eugene O’Neill completed The Iceman Cometh and Long Day’s Journey Into Night. It was originally intended as part of a series of eight one-act plays given the overall title By Way Of Orbit.

It was the author’s plan that the central character in each piece would examine their relationship to a person who had died while another character would do almost nothing but listen. O’Neill commented: ‘Via this monologue you get a complete picture of the person who died – his or her whole life story – but just as complete a picture of the life and character of the narrator.’ Hughie is the only manuscript from the collection that survives, the author having destroyed his notes and drafts for the other plays.

Although completed in the early forties, the play did not receive its world premiere until 1958, in a production at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Sweden with Bengt Eklund as Erie Smith. Five years later, in 1963, Burgess Meredith played Erie in a production at Bath’s Theatre Royal in England.

Hughie was first performed on Broadway in 1964 with Jason Robards in the title-role, the actor receiving a Tony Award nomination for his performance. Robards revived his portrayal in 1975 in California, playing opposite Jack Dodson as Charlie Hughes. The pair reprised their roles three further times: at the Hyde Park Festival in 1981; on television for PBS in 1984; and finally at the Trinity Repertory Theatre in 1991.

The play has been produced two more times on Broadway since the 1964 production starring Robards. Ben Gazarra played Erie, gaining a Tony Award nomination for his performance, in 1975 and Al Pacino directed and starred in a production at the Circle in the Square Theatre in 1996. Other notable productions include Brian Denehey in the title-role at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 2010.

The play in context

Times Square in the 1920s

Before becoming an entertainment and business district, Times Square – formerly known as Longacre Square – housed the carriage-making industry. The area acquired its current name in 1904 when The New York Times moved its headquarters to the newly built Times Building. With the proliferation of cars and the completion of a subway that connected it to Grand Central, the area changed rapidly. After World War I, Times Square grew dramatically, becoming a cultural hub of theatres, music halls and upmarket hotels.

The nightlife in Times Square attracted many celebrities. Especially popular at the time were vaudeville performances that featured a range of acts performing together in one show. The most famous was possibly the Ziegfeld Follies, which was known for its beautiful chorus girls in elaborate costumes.

During this period Times Square was also besieged by crime and corruption, in the form of gambling and prostitution. Gangsters dominated local nightclubs, often bribing the police. When Prohibition came into effect, many of the legitimate cabarets and restaurants in the area closed and were replaced by cinemas (movie theatres) and tourism that would attract advertisers to bring in the bright lights that are associated with Times Square today. This is how Broadway earned its nickname, ‘The Great White Way’, as it was the first street in America to be fully lit by electric light.

Prohibition

In 1920 the 18th Amendment was ratified to the US Constitution banning the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating liquors, and thus beginning a period in American history known as ‘Prohibition’.

Prohibition was the result of a widespread temperance movement, born out of religious roots and a belief that excess alcohol consumption was responsible for society’s moral corruption. It led to an increase in the illegal production and sale of liquor, known as ‘bootlegging’, as well as illegal bars, known as ‘speakeasies’. It was a time that invited clandestine behavior and saw an accompanying rise in gang violence and other criminal activity.

Prohibition was difficult to enforce, especially as consumption of alcohol itself was not illegal, and eventually had a negative impact on the US economy. Thousands of jobs were lost through the closure of distilleries and breweries. Restaurants and theatres saw a sharp decrease in revenue and the government lost valuable income from excise taxes. This, coupled with the many difficulties arising from the Great Depression, led to waning support for Prohibition.

In early 1933 Congress proposed a 21st Amendment to the Constitution that would repeal the 18th Amendment. It was ratified by the end of that year, bringing the Prohibition era to a close.

Gangsters

Gangsters played a prominent part in 1920s New York City. One such figure, referred to in Hughie, is Arnold Rothstein. He was a legendary gambler, notorious for rigging the 1919 World Series. Having built his empire on fixed horse races, card games and Manhattan gambling houses, Rothstein diversified his business during Prohibition to include the illegal sale of alcohol. He moved into bootlegging, selling drugs, racketeering, loan-sharking and everything that went with it, including bribery and murder.

Rothstein was nicknamed ‘The Brain’ for his sharp intellect and polished demeanor. He associated with other famous gangsters, notably Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond, Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano and Dutch Schultz, as well as politicians and legitimate businessmen. Rothstein was known to have conducted his business at Lindy’s Restaurant on Broadway and 49th Street, just a few blocks from Erie’s rundown hotel – and the Booth Theatre, where MGC’s 2016 production of Hughie was staged. Rothstein was eventually murdered in 1928 by rival gamblers for not paying debts.

Why is it that the Night Clerk obsessively asks Erie if he knows ‘The Big Shot’ Rothstein? And why is it that both characters idolise his gangster lifestyle? To them Rothstein represents the possibility of power, wealth, glamour and respect that they are so lacking in their own lives. He also symbolises, albeit in a corrupted fashion, the realisation of the American Dream, to which so many people aspired.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression was a worldwide recession that severely affected America throughout the 1930s, following the crash of the Wall Street Stock Market in October 1929. It had a significant impact on individuals in cities, where unemployment reached as high as 25% in 1932. Inner-city men over the age of 45 with few skills were one of the key demographics to be worst affected.

Hoovervilles – named after the then American President, Herbert Hoover – formed in urban centres, where the homeless created slums made of cardboard and wood. Both Central and Riverside parks were overrun with such shanty towns.

Economic depression is often accompanied by emotional depression. By setting Hughie on the eve of The Great Depression and focusing on his characters’ desolation, O’Neill foreshadows the destitution that would ravage the country for the next decade.

In Hughie, Eugene O’Neill incorporates slang vernacular from the 1920s. Below are definitions of some of the terms used in the play.

Bangtails

Horses – usually refers to those whose tails have been cut

Big Stem

Broadway

Brooklyn Boys

Gangsters – many mafia families were based in Brooklyn in the 1920s

Burg

An ancient walled town

Dead wrong Gs

Are owed thousands of dollars

Deef

Deaf

Follies, scandals, frolics

All refer to the glamorous showgirls from the Zeigfield theatre revues

Hanging on the ropes

Boxing metaphor indicating that a fighter is nearly beaten

In the bucks

Rich with cash

In the sticks

In a small, rural town

Jack

Money

Man o’ War

Considered one of the greatest thoroughbred race horses of all time. During his career, just after World War I, he won 20 of 21 races and close to $250,000 prize money.

Off on a bat

To go on a spree

On the lam

On the run – usually from the authorities

Piker

Small-time gambler

Punk

Worthless, bad

Put the bite on

Ask for money

Sap

A foolish or gullible person

Shotgun ceremony

A hurried wedding involving a pregnant bride

Took a run-out powder

Left somewhere in a hurry

Welshing

To renege or fail to honour – as in a debt or obligation incurred through a promise or agreement

Further Reading

Hughie by Eugene O’Neill (Dramatists Play Service Inc., 1982).

The text of the play.

Bibliography

The following biographies of Eugene O’Neill were consulted in preparation for MGC’s production of Hughie:

Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts by Robert M. Dowling (Yale University Press, 2014)

O’Neill: Life with Monte Cristo by Arthur & Barbara Gelb (Applause Books, 2000)