Peter and Alice

“Of course that’s how it begins: a harmless fairy tale to pass the hours.”

About the work

2013

Welcome to the world premiere of Peter and Alice by John Logan, produced by the Michael Grandage Company

When Alice Liddell Hargreaves met Peter Llewelyn Davies at the opening of a Lewis Carroll exhibition in 1932, the original Alice in Wonderland came face to face with the original Peter Pan.

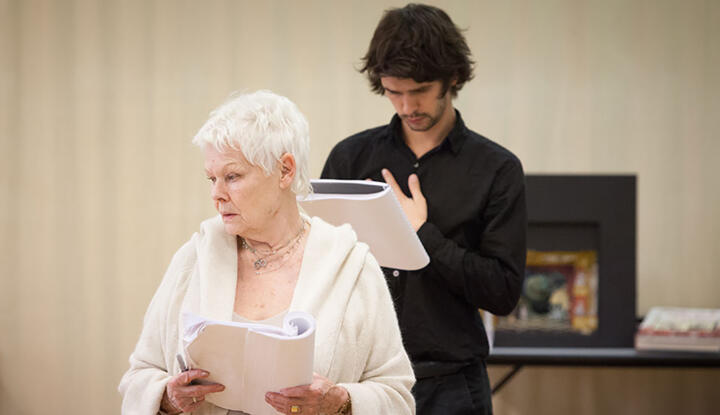

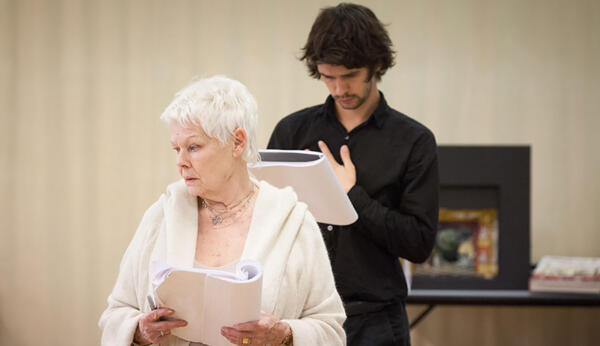

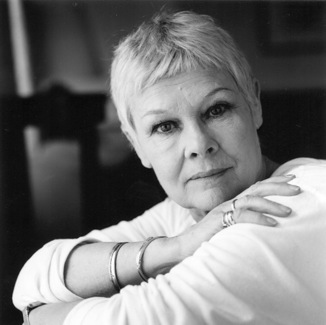

Judi Dench plays Alice and Ben Whishaw plays Peter in John Logan’s first new play since Red, which won six Tony Awards in 2010. In Peter and Alice, enchantment and reality collide as this brief encounter lays bare the lives of these two extraordinary characters.

“This is a continuation of a strong relationship with John Logan the writer that started on Red at the Donmar. His next play goes darker and deeper, taking up multiple themes in one scenario – which is that the real‑life Alice in Wonderland did briefly meet the real‑life Peter Pan in a bookstore in 1932. In Logan’s imagined discussion these two real‑life figures talk, among other matters, about the trauma of being something that the public plays onto them, and how each of them have coped with it in very different ways. The audience gets the joy of receiving all the affection and visual sensation of revisiting two beloved fictional characters through the prism of their real, darker selves.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

London, 1932.

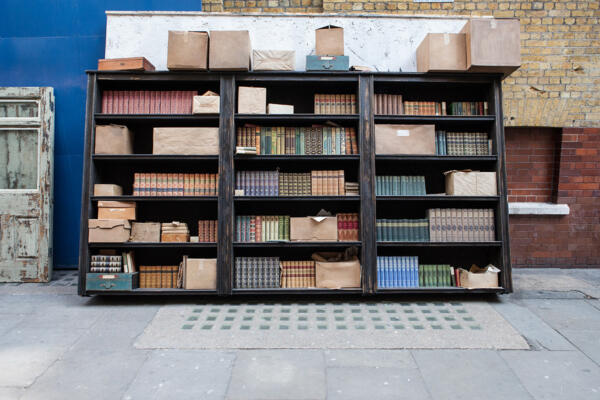

In the backroom of the Bumpus bookshop at 350, Oxford Street a nervous-looking man in his thirties, Peter Llewelyn Davies, waits anxiously for the guest-speaker at the opening of a Lewis Carroll exhibition, whom he is to introduce – 80-year-old Alice Liddell Hargreaves.

A publisher by trade, Peter wants to commission Alice to write her memoirs and plans to use his particular circumstances to persuade her. They share a unique bond, for both Peter and Alice were the inspiration for two of the most famous figures in children’s literature – Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland.

But while Peter encourages the older woman to open a door onto her childhood, Alice would rather forget. Despite her age, she proves a formidable character, rebuffing Peter’s advances and the young man struggles to make a connection.

Though Alice may be done with the past, it isn’t done with her and very soon reality and fantasy collide as both Peter and Alice are plunged into a world largely of their own imagining…

Together they journey through the dark recesses of the authors JM Barrie’s and Lewis Carroll’s minds, through the pain and loss of the First World War, to adulthood, all the while hoping to emerge unscathed on the other side. Alice may know the way to Wonderland but can Peter join her there?

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

| Director | Michael Grandage |

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Lighting Designer | Paule Constable |

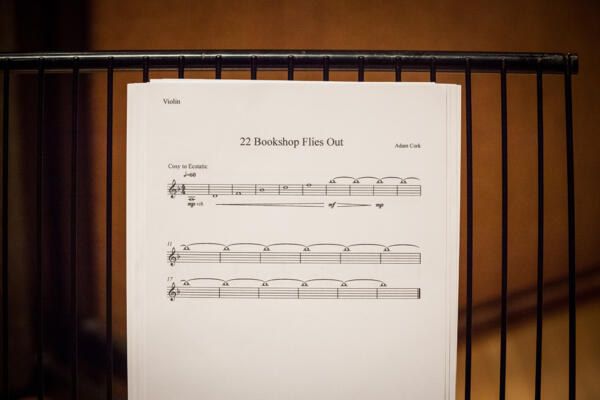

| Composer & Sound Designer | Adam Cork |

| Casting Director | Toby Whale |

| Wig & Hair Designer | Campbell Young |

| Production Manager | Paul Handley |

| Company Stage Manager | Sophie Gabszewicz |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Clare Fisher |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Oliver Bagwell Purefoy |

| Dialect Coach | Penny Dyer |

| Props Supervisor | Celia Strainge |

| Costume Supervisor | Stephanie Arditti |

| Head of Wardrobe | Tim Gradwell |

| Head of Wigs & Make-Up | Gemma Flaherty |

| Deputy Head of Wardrobe | Charlotte Stidwell |

| Wardrobe Assistant | Rachael McIntyre |

| Associate Director | Timothy Koch |

| Associate Set & Costume Designer | Lee Newby |

| Associate Set & Costume Designer | David Woodhead |

| Associate Lighting Designer | Rob Casey |

| Associate Sound Designer | Yvonne Gilbert |

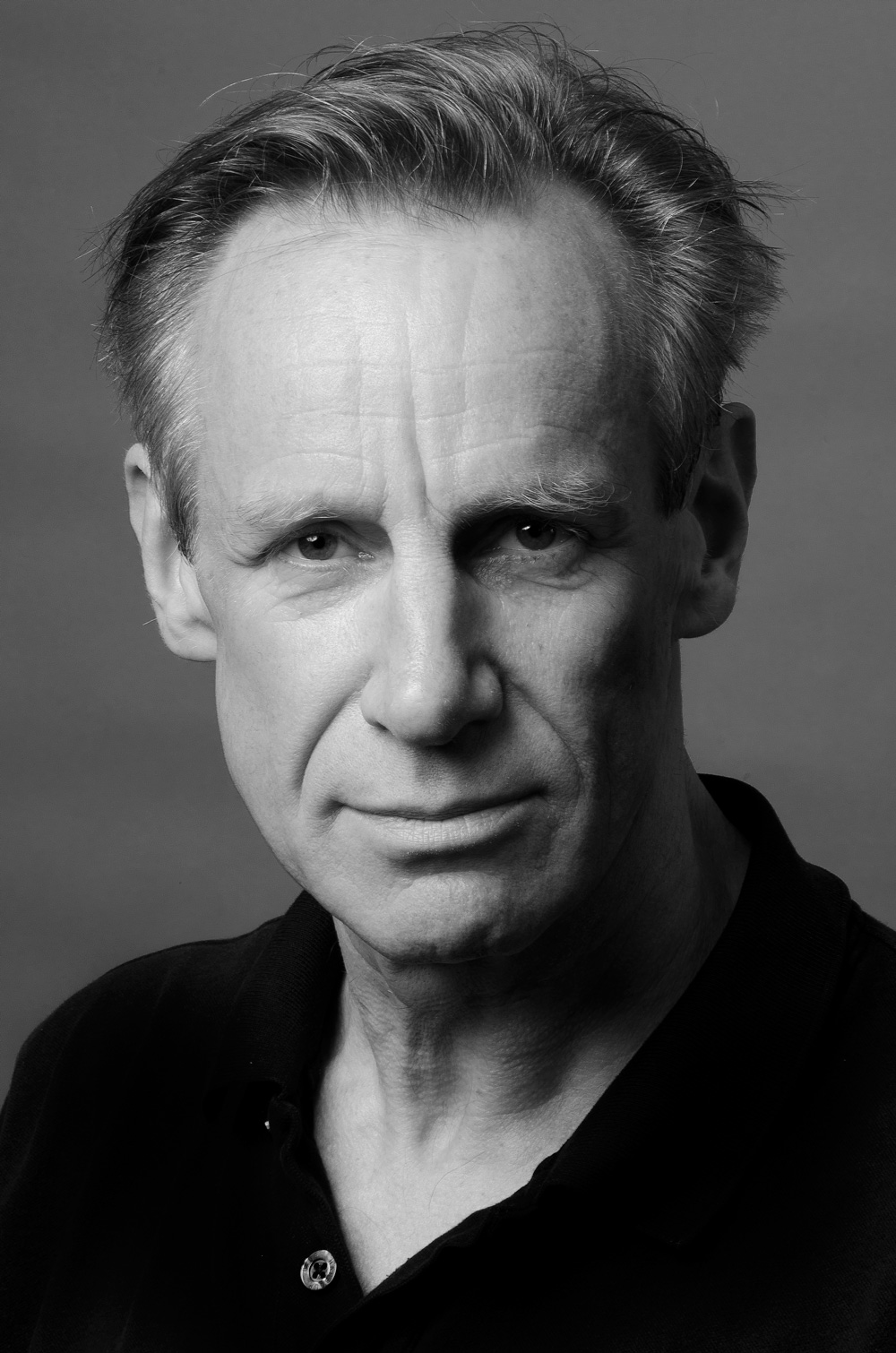

John Logan

John Logan received the Tony, Drama Desk, Outer Critics’ Circle and Drama League awards for his play Red, directed by Michael Grandage. The play premiered at the Donmar Warehouse in London and at the Golden Theatre on Broadway. Red has subsequently been seen in more than 80 productions across the USA and in over thirty foreign countries.

He is also the author of more than a dozen plays, including Never the Sinner and Hauptmann. His new play I’ll Eat You Last premiered on Broadway in April 2013.

As a screenwriter, Logan has been three times nominated for an Oscar and has received a Golden Globe, BAFTA and WGA award. His film work includes Skyfall, Hugo, The Aviator, Gladiator, Rango, Coriolanus, Sweeney Todd, The Last Sumurai, Any Given Sunday and RKO 281. He is currently writing the next two James Bond films.

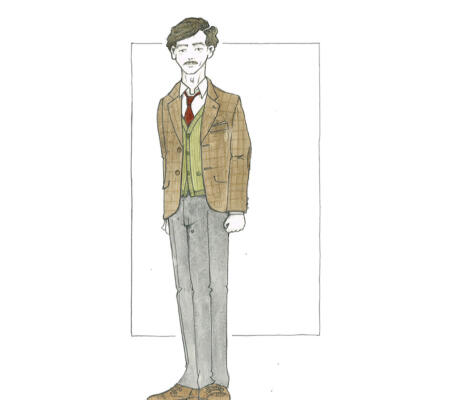

Peter Llewelyn Davies (Ben Wishaw)

Thirties, wears a ‘conservative suit’. A thoughtful and articulate man, he may look nervous but his apparent frailty belies a searching intelligence and persuasive rhetoric.

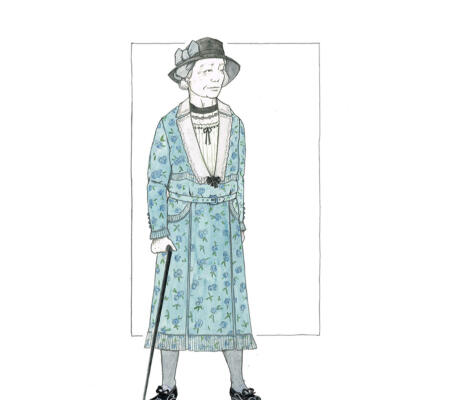

Alice Liddell Hargreaves (Judi Dench)

80-years-old. A poised and stately older woman, though she walks with a stick her mind remains strong, her observations sharp – ‘She is like iron’. Beneath her armour, however, is a vulnerability and fear of old age.

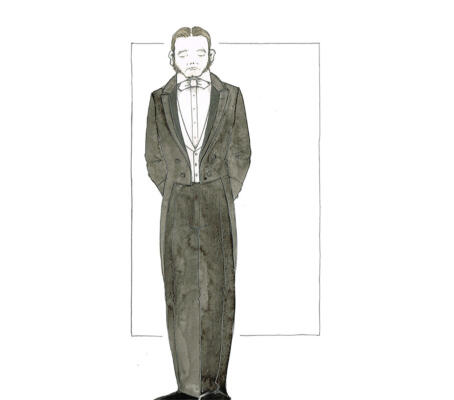

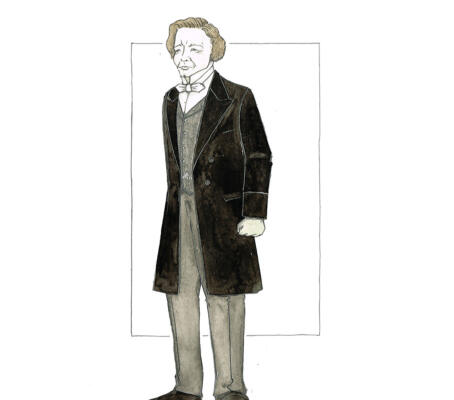

Lewis Carroll (Nicholas Farrell)

Middle-aged. ‘He’s slanted, awkward, partly deaf and painfully shy.’ A gifted storyteller with a great command of the English language, he suffers from a stammer, which is worse when he’s nervous.

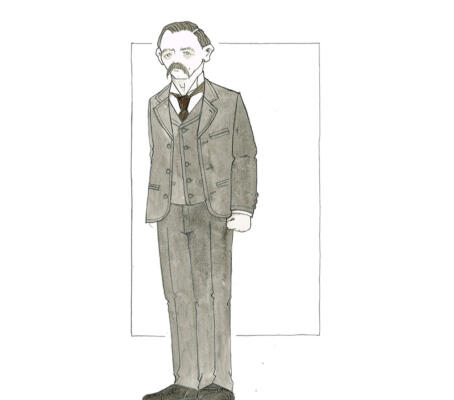

James Barrie (Derek Riddell)

Middle-aged. ‘He’s a stunted, sad, inspiring Scotsman.’ Another wordsmith, like Carroll he’s an intoxicating but lonely figure. Capable of extreme kindness and acts of generosity, he can be equally cutting and cruel.

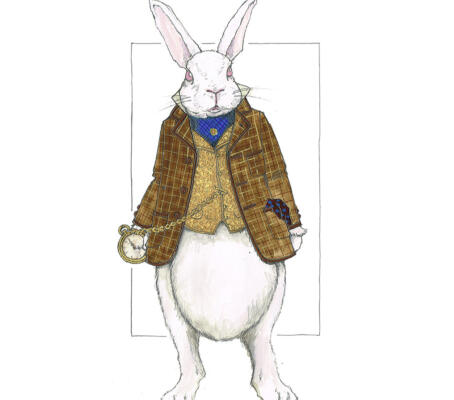

Peter Pan (Olly Alexander)

An eternal child – ‘The boy who wouldn’t grow up’. ‘He’s full of bravado and nerve and looks exactly as you imagine Peter Pan to look.’ Charming and effervescent, his scorn for the weakness of others, especially adults, borders on contempt.

Alice in Wonderland (Ruby Bentall)

10-years-old. ‘She’s a bold and curious girl.’ More sympathetic than Peter Pan, she too delights in stories, continually asking questions about the world around her. She and Peter Pan ‘interact, examine, imitate, and shadow’ their real-life counterparts.

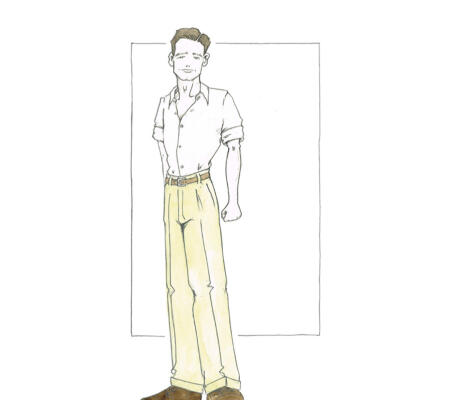

Arthur Davies (Stefano Braschi)

Middle-aged, Peter’s father. A barrister by profession, he loses his job when he becomes ill with terminal cancer. Suspicious of Barrie’s interest in his family, he’s anxious about the future for his wife and five sons.

Reginald Hargreaves (Stefano Braschi)

Twenties, Alice’s suitor and eventual husband. ‘He’s a good-looking, athletic, hearty young man.’ From a privileged background, ‘Reggie’ is enthusiastic and nervous in equal measures and desperate to win Alice’s affection.

Michael Davies (Stefano Braschi)

Twenties, Peter’s younger brother. ‘He’s a beautiful and poetic young man, fragile.’ The true real-life inspiration for Peter Pan, he’s also Barrie’s favourite. Michael is devoted to him, in spite of his occasionally jealous and unkind comments.

The following is an extract from Dominic Cavendish’s interview with John Logan, published in The Telegraph, 19th March 2013

As with Red, the idea for which hit him on encountering Rothko’s Seagram murals at Tate Modern in 2007, so Peter and Alice was prompted by a chance find, [John Logan] explains. Thumbing through a copy of a biography called The Real Alice, Logan came across a mention of a meeting at Bumpus bookshop, Oxford Street, between Alice (then 80) and Peter (then 35). It took 20 years after that discovery, ‘in Adelaide of all places’, for the play to reach fruition. The resulting multi-character drama will interweave fact and fiction and take wing across the worlds of Neverland and Wonderland.

Quite a task and a responsibility, given how treasured those tales are, and how wary one should be about misrepresenting the dead. ‘It’s incredibly difficult,’ he admits, ‘when you’re dealing with historical or literary material. The exultation lies in finding the poetry – but you can’t act in bad faith. You can only torque history so far before it snaps.’

The true story of the five Davies brothers, whom JM Barrie befriended in Kensington Gardens and became a surrogate father to, is as heartbreaking as the art they inspired in innocent, happier days: the eldest, George, died in the trenches; Michael, the second youngest, committed suicide aged 20; and Peter – the middle child – threw himself in front of a Tube train in 1960 at the age of 63.

The case of Alice Hargreaves (née Liddell) is a little cheerier – although she lost two sons in the First World War and wound up so cash-strapped following her husband’s death that she sold off the original 1864 manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground.

The play will inevitably focus on how its two principal characters came to be overshadowed by their ever-youthful literary incarnations and by the men who moulded them into fiction. Logan is after universal themes too, though.

‘With Red I was interested in the passing of a generation and the relationship between fathers and sons. With Peter and Alice, the organising principle for me in a way was: what is it to grow up? What do you gain, what do you lose? Is there a moment when you can say to yourself ‘I am no longer a child’?’

Peter and Alice by John Logan (Oberon, 2013)

The text of the play

The following books were in the rehearsal room for Peter and Alice:

- Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens – Illustrations by Arthur Rackham

- JM Barrie and The Lost Boys – The Real Story Behind Peter Pan – Andrew Birkin

- Peter Pan on Stage and Screen 1904-2010 – Bruce K. Hanson

- Arthur Rackham – A Life with Illustrations – James Hamilton

- The Real Alice – Anne Clark

- The World of Alice – Pitkin Guides

- Alice in Wonderland – Through the Visual Arts – Gavin Delahunty

- Alice Illustrated – 120 Images from the Classic Tales of Lewis Carroll – Jeff A. Menges

- Lewis Carroll – Anne Higonnet

- Lewis Carroll – Thames & Hudson Profile

- Lewis Carroll – Photographer – Helmut Gernsheim

- Tenniel’s Alice – Eleanor Garvey

- Toy Theatres of the World – Peter Baldwin