Red

About the work

2018

Welcome to the Michael Grandage Company’s production of Red by John Logan

Under the watchful gaze of his young assistant, and the threatening presence of a new generation of artists, Mark Rothko takes on his greatest challenge yet: to create a definitive work for an extraordinary setting.

Based on the original Donmar Warehouse production, this new production of Red is the first ever UK revival since MGC Artistic Director Michael Grandage directed the premier in 2009. The production went on to win six Tony Awards including Best Play.

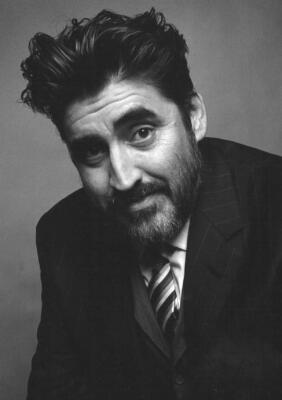

Award-winning stage and screen actor Alfred Molina reprises his critically acclaimed performance as the American abstract expressionist painter Mark Rothko. He is joined by rising star Alfred Enoch, of US television drama series How to Get Away With Murder, as his assistant Ken.

Red reunites John Logan and Michael Grandage following Peter and Alice with Judi Dench and Ben Whishaw, which formed part of MGC’s inaugural season in the West End in 2013, and their feature film Genius.

“The play is about two years in the life of Mark Rothko, the great abstract expressionist. It’s about the relationship between him and his assistant in the studio, and it’s most particularly about art in the biggest sense of the word – why art is important and why being serious about art is a good thing. The whole debate at the centre of John Logan’s play is about how you look at something, not just what you see, but what you discuss with yourself when you see it. It has this colossal debate in 90 minutes.

We’re making a new production for the West End, responding to the world we are in now in 2018. It’s should feel like a response to the time we are living in now. We have a wonderful opportunity with Alfred Enoch, who’s taking the role of Ken, to look at the play in a very different way. So the whole thing is going to feel considerably different. The West End is the one place it hasn’t played and that’s why we want to do it.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

New York, 1958.

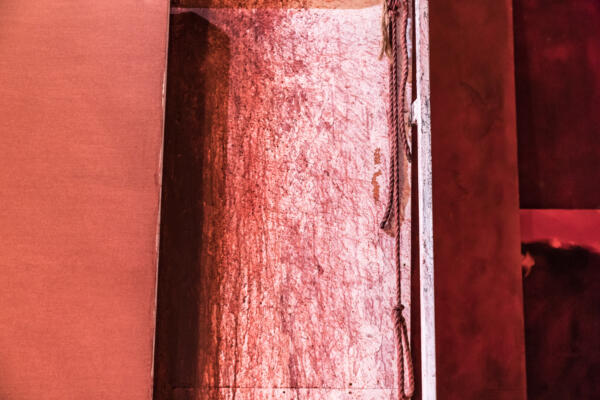

Celebrated artist Mark Rothko is at the height of his fame having just accepted a commission to paint a series of murals for the exclusive Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building on Park Avenue. To help him in his work he’s employed a new assistant, Ken, himself an aspiring artist. Rothko plans to paint thirty or more canvases and then choose the ones that work best together. It’s a time-consuming process, one that requires careful deliberation.

As Rothko studies the paintings he questions Ken on his attitude to art and the young assistant, in turn, challenges the older artist’s perception of contemporary culture – contrasting Mozart with Chet Baker, Rothko with Andy Warhol. Rothko feels increasingly under threat from this new generation of artists – Jasper Johns, Frank Stella and Roy Lichtenstein – ready to replace him just as he and his contemporaries replaced the Cubists thirty years before.

Will Rothko and his paintings survive? How does an artist create a body of work that lives on? Perhaps the ‘Seagram Murals’ will be his lasting legacy, but is the venue the right setting for them? And are the clientele the right viewers?

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

| Director | Michael Grandage |

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Lighting Designer | Neil Austin |

| Sound Designer | Adam Cork |

| Casting Director | Anne McNulty |

| Associate Director | Josh Seymour |

| Production Manager | Patrick Molony |

| Company & Stage Manager | Greg Shimmin |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Nicole Walker |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Rhiannon Harper |

| Costume Supervisor | Mary Charlton |

| Props Supervisor | Celia Strainge |

| Dialect Coach | Joan Washington |

| Head of Wardrobe | Charlotte Stidwell |

| Wardrobe Assistant | Helen Tams |

John Logan

John Logan received the Tony, Drama Desk, Outer Critic Circle and Drama League awards for his play Red. This play premiered at the Donmar Warehouse in London and at the Golden Theatre on Broadway. Since then Red has had more than 200 productions across the US and has been presented in over 30 countries. He is the author of more than a dozen other plays including Peter and Alice, I’ll Eat You Last: A Chat with Sue Mengers and Never the Sinner. He also co-wrote the book for the musical The Last Ship. As a screenwriter, Logan has been three times nominated for the Oscar and has received a Golden Globe, BAFTA, WGA, Edgar, and PEN Center award. His film work includes Skyfall, Spectre, Hugo, The Aviator, Gladiator, Rango, Alien: Covenant, Genius, Coriolanus, Sweeney Todd, The Last Samurai, Any Given Sunday and RKO 281. He created and produced the television series Penny Dreadful for Showtime.

Mark Rothko (Alfred Molina)

American painter, 50s or older

“He wears thick glasses and old, ill-fitting clothes spattered with specks of glue and paint.”

A temperamental man with strong opinions, especially about art, his volatility hides a vulnerability – the fear of becoming redundant and ultimately being replaced.

Ken (Alfred Enoch)

Rothko’s new assistant, 20s

A thoughtful young man with a troubled past, he’s an aspiring artist eager to learn more. Nervous at first around Rothko, Ken slowly grows in confidence and is ultimately able to challenge the older man.

Red by John Logan (Oberon, 2018)

The text of MGC’s 2018 production of the play at Wyndham’s Theatre

The following is a list of books about Mark Rothko, his life and work, and the cultural context of the play, which were in the rehearsal room for the original production in 2009:

- The Artist’s Reality – Philosophies of Art by Mark Rothko (Yale University Press, 2004)

- Writings on Art by Mark Rothko (Yale University Press, 2006)

- Mark Rothko (Skira, 2007)

- Mark Rothko (National Gallery of Art Washington/Yale Catalogue, 1998)

- Rothko ed. by Achim Borchardt-Hume (Tate, 2008)

- Mark Rothko – A Biography by James E.B. Breslin (University of Chicago Press, 1993)

- The Legacy of Mark Rothko by Lee Seldes (Da Capo Press, 1996)

- Mark Rothko in New York by Diane Waldham (Guggenheim Museum, 1994)

- Seeing Rothko ed. by Glenn Phillips and Thomas Crow (Getty Publications, 2005)

- Fifties Forever – Popular Fashions for Men, Women, Boys and Girls by Roseann Ettinger (Schiffer, 1998)

- Fashionable Clothing from the Sears Catalogs Late 1950s by Joy Shih (Schiffer, 1997)

- Young Chet by William Claxton (Schirmer Art Books, 1993)