The Lemon Table

About the work

2021

Wiltshire Creative, Malvern Theatres, Sheffield Theatre and HOME in association with the Michael Grandage Company present the world premiere of The Lemon Table by Julian Barnes

A play in two parts, The Lemon Table celebrates a love of music, live performance, and life itself. In the first half we are introduced to an obsessive concert goer who goes to unorthodox lengths to enjoy his evening. In the other, the concert’s composer reflects on the music he has created – his successes, his failures, and the life he has lived.

A darkly funny and beautifully written evening that celebrates our return to live performance and the artists who make it.

“When Ian McDiarmid suggested The Lemon Table to continue our thirty year working relationship, there was no doubt in my mind that it offered us both an opportunity, post-pandemic, to return to the theatre in an incredibly focussed way with a distilled piece of work for one person. These two short plays add up to a kind of tone poem where the experience is greater and deeper than the relatively short 60 minute running time. Indeed, it offered audiences a level of existential debate that so many of us had gone through over nearly two years without access to live performance.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

Two men separated in time by several decades but united by their advancing years: the composer and the connoisseur.

One, now in his seventies, has been enjoying classical concerts for years, his only frustration the coughers and talkers in the audience who threaten to spoil his evening’s entertainment.

The other, in his nineties, has withdrawn into silence while his critics and admirers await the final coda to his illustrious career – the much-anticipated 8th symphony.

Both strive to maintain their inner and outer peace while attempting to reconcile the mistakes of the past with an uncertain future…

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

| Writer | Julian Barnes |

| Directors | Michael Grandage & Titas Halder |

| Set & Costume Designer | Frankie Bradshaw |

| Lighting Designer | Paule Constable |

| Sound Designer | Ella Wahlström |

| Associate Lighting Designer | Ryan Day |

| Production Manager | John Titcombe |

| Company and Stage Manager | Kate Schofield |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Lucy Bradford |

| Costume Supervisor | Henrietta Worrall-Thompson |

| Set Construction | Tim Reed & Daniel Gent |

| Scenic Art | Richard Nutbourne, Scenic Studio |

| Technical Manager | Barny Meats |

| Deputy Technical Manager | Dave March |

| Senior Technicians | Matt Bird & Michael Scott |

| Technicians | Jonathan Cox & Matt Gill |

| Rehearsal & Production Photographer | Marc Brenner |

| Trailer | The Other Richard |

| Poster Photography | Johan Persson |

| Poster Design | AKA |

Julian Barnes

Julian Barnes is the author of twenty-four books including The Man in the Red Coat. He received the Man Booker Prize for The Sense of an Ending and has also received the Somerset Maugham Award, the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, the David Cohen Prize for Literature, and the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; the French Prix Médicis and Prux Femina; the Austrian State Prize for European Literature; the Jerusalem Prize; and in 2017 he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur by the French government.

His work has been translated into more than forty languages. He lives in London.

(In order of speaking)

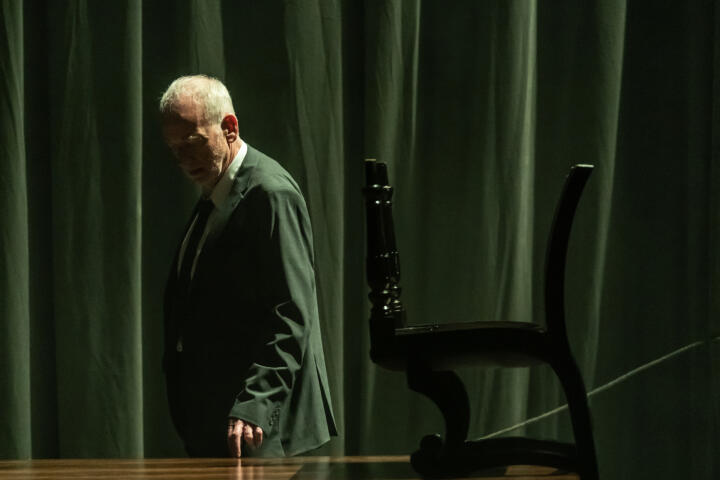

1st man (Ian McDiarmid)

A concert goer

“A man in his early seventies. Dark suit, loosened, undecorated tie, spectacles.”

A fastidious man, precise in his thoughts and speech, he is often irritable and easily roused to anger.

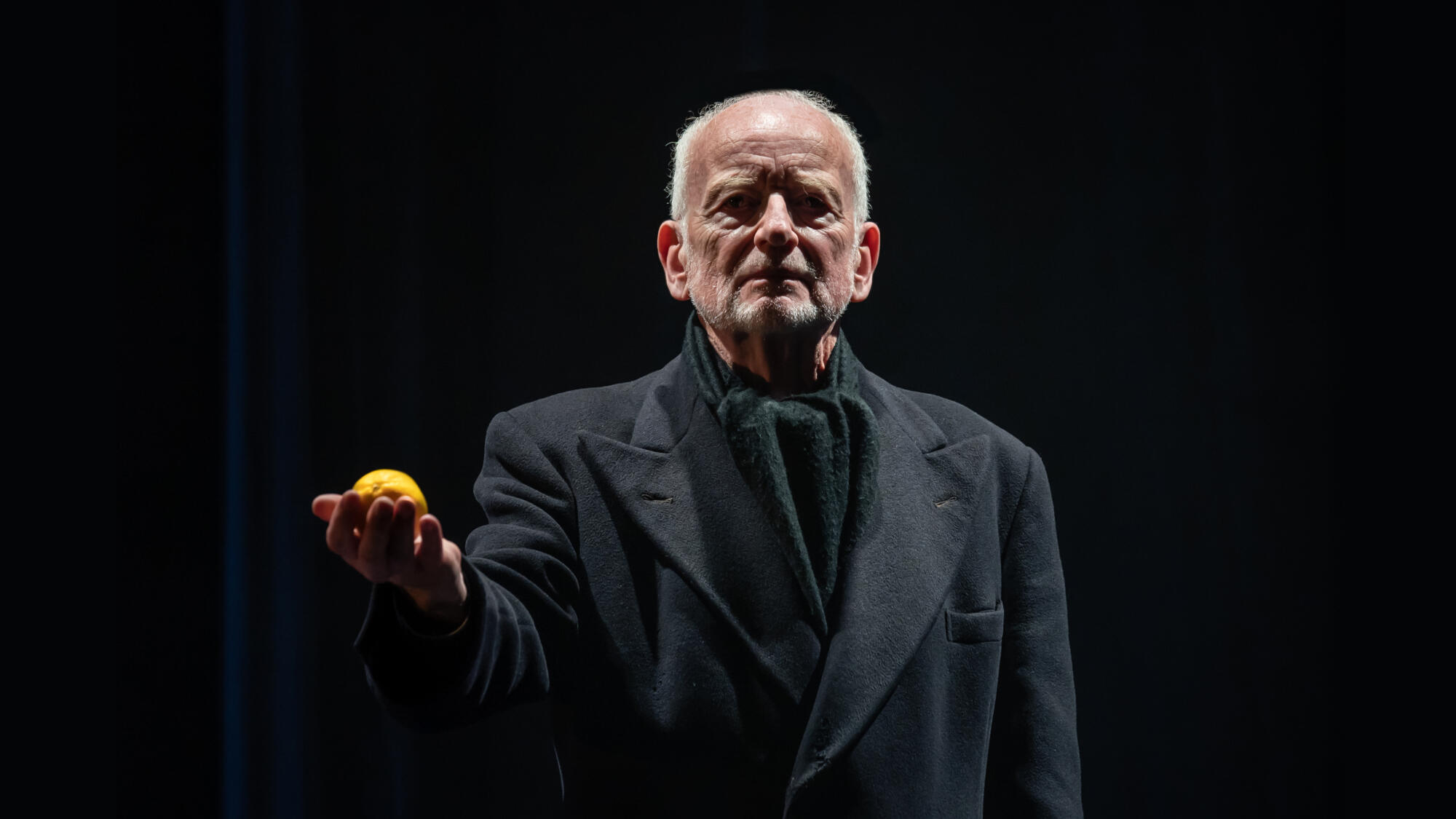

2nd man (Ian McDiarmid)

A composer

“A man in his early nineties, in a black coat.”

A solitary figure, seemingly happiest in his own company.