Henry V

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.”

About the work

2014

Welcome to the Michael Grandage Company’s production of Henry V by William Shakespeare

Can the King of England hold his nerve to embrace his duty, command his men and lead his country to victory in France? Shakespeare’s great play of nationhood investigates the bloody horrors of war and the turbulence of a land in crisis.

Jude Law and Michael Grandage continue their collaboration that began with Hamlet in 2009. Law also appeared in the Donmar Warehouse’s award-winning production Anna Christie, as part of Grandage’s final season as Artistic Director.

“I’d already seen Jude Law in ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore, Faustus and Ion when we did Hamlet – I saw him as a classical actor. This has come entirely out of that relationship – we wanted it to continue. It was a question of which part. Henry V is a relatively young man’s role and Jude is getting older and wanting to do that before he does any other. That was one motivation.

The play itself has the whole question of nationhood at its centre, while looking at the issue of great responsibility sitting on one man’s shoulder. The context of how we explore it is something we’ve already started discussions about and will continue doing so for the best part of six or seven months until we hone down the right environment but the themes will never change and will always be pertinent whether we as a country are or are not at war. The world’s at war, usually.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

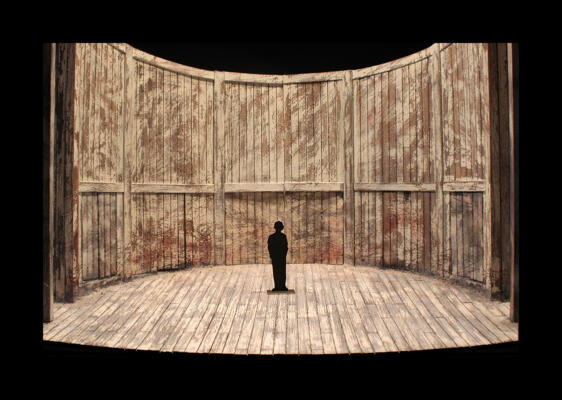

| Director | Michael Grandage |

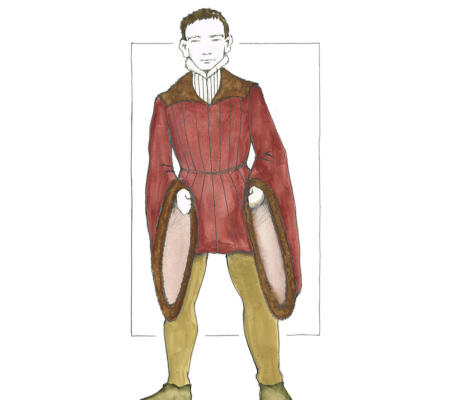

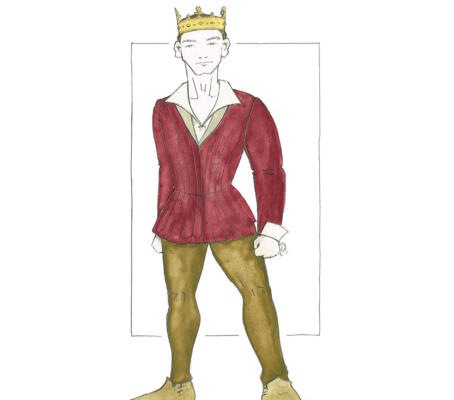

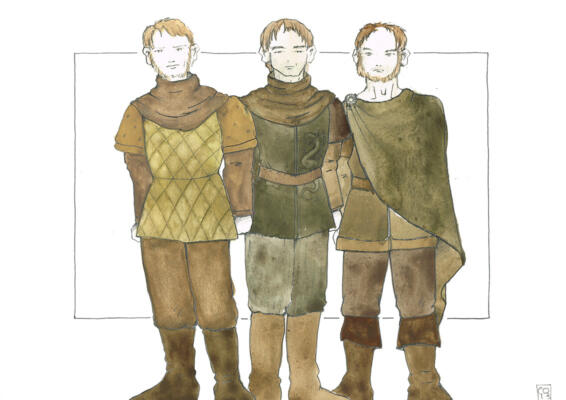

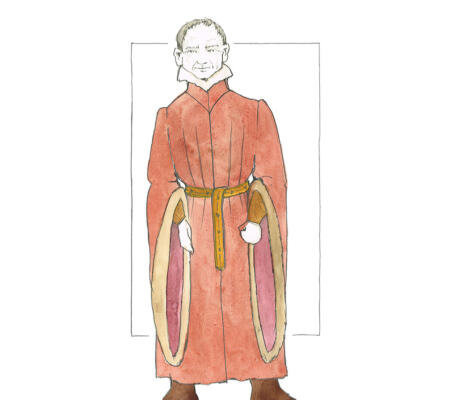

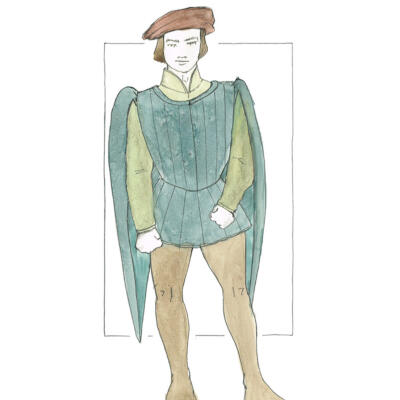

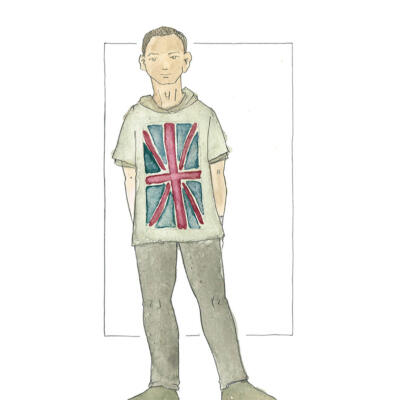

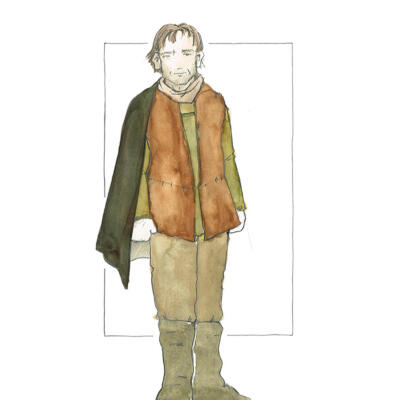

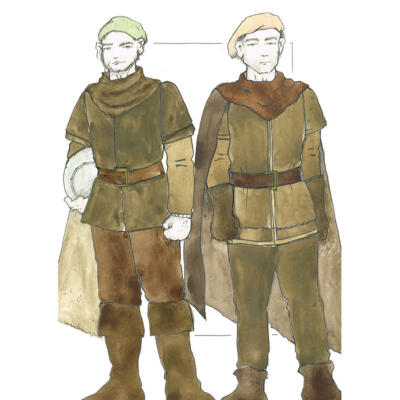

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Lighting Designer | Neil Austin |

| Composer & Sound Designer | Adam Cork |

| Casting Director | Anne McNulty |

| Movement Director | Michael Ashcroftt |

| Wig & Hair Designer | Campbell Young |

| Production Manager | Paul Handley |

| Co-Production Manager | Anna Anderson |

| Company Stage Manager | Sophie Gabszewicz |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Rhiannon Harper |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Ralph Buchanan |

| Props Supervisor | Celia Strainge |

| Costume Supervisor | Natasha Ward |

| Dialect Coach | Penny Dyer |

| Head of Wardrobe | Tim Gradwell |

| Head of Wigs & Make-Up | Gemma Flaherty |

| Deputy Head of Wardrobe | Charlotte Stidwell |

| Wardrobe Assistant | Rachael McIntyre |

| Dresser | Amanda Wilde |

| Associate Director | Lisa Blair |

| Associate Set & Costume Designer | Lee Newby |

| Associate Lighting Designer | Derek Anderson |

| Associate Sound Designer | Giles Thomas |

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was born in April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon and educated at the town’s grammar school. He had been working as playwright and actor in London’s playhouses for some five years by the mid-1590s, when A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written and performed, and had published two narrative poems, The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis. His Sonnets, privately circulated and dating from 1593 and 1603, were first printed in 1608. A series of romantic comedies were performed between 1597 and 1601: The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado about Nothing, As You Like It and Twelfth Night. These years also saw the two parts of King Henry IV, King Henry V, King John and Julius Caesar, and Hamlet, thought to date from around 1600. Between 1602 and 1606 came a number of plays that were barely comedies but not clearly tragedies: Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure and All’s Well That Ends Well. From the same period are the great tragedies: Othello, King Lear, Hamlet, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. In later years he favoured stories with a freer, romantic range, the last of these being The Tempest (1610-11). His last known dramatic works were written in collaboration with John Fletcher: The Two Noble Kinsmen and All Is True (also known as King Henry VIII), performed in 1613. After retiring to Stratford-upon-Avon Shakespeare died there on 23 April 1616.

A Restless History

Shakespeare’s ambiguous handling of one of England’s most celebrated monarchs has led to a long fascination with Henry V. Russell Jackson explores the play’s continuing appeal.

Henry V was probably written in 1599 and first published in 1600, at around the same time as Hamlet (written between 1598 and 1600). The culminating episode of the series represented by Richard II (1595) and the two parts of Henry IV (1597-98), the play has often been recognised as profoundly ambiguous, celebrating valour and leadership while at the same time conveying the loss, pain and brutality of war. In this it resembles such films of military conflict as Saving Private Ryan or the TV series Band of Brothers. For all their claims to an unflinching presentation of the miseries and dangers (and brutalities) of warfare, it is often difficult to separate the impact of these films from the audience’s desire to see their heroes succeed in a ‘just war’. Similarly, with the two feature films of Shakespeare’s play – Laurence Olivier’s in 1944 and Kenneth Branagh’s in 1988 – the excitement and glamour of the entertainment has been thought to cancel out their thoughtfulness and subtlety. Is Henry V, then, unavoidably glamorising military success? When he gives the tactically legitimate command that ‘every man should kill his prisoner’ to stop the French forces regrouping, is Henry really the ‘good king’ described by the play’s own enthusiastic military historian, Captain Fluellen? Or does the vivid, warlike energy of his threats to the citizens of Harfleur – ‘I will not leave the half-achieved Harfleur/Till in her ashes she lies buried’ – reflect a ruthlessness of spirit within Henry that the play endorses?

It may be better to think of it as a restless work. It constantly reminds us, through the Chorus’s speeches, of its own artifice, undermining idealism with the pragmatism and at times ruthless decisiveness of the central character, and shifting its ground so that the point of view of one character or group of characters is qualified by that of another. ‘Now all the youth of England are on fire,’ says the Chorus, but the next scene takes us to the street-life of Eastcheap and the kind of company Henry has put behind him. The battle of Agincourt is represented by episodes around the conflict itself, including the scene between the abject French knight Monsieur Le Fer and Pistol, the self-styled ensign (‘ancient’) who is a ‘counterfeit cowardly knave’ with a taste for stage-play rhetoric. And at the very end the Chorus reminds us that although Henry’s successful campaign and subsequent dynastic marriage achieved ‘the world’s best garden’ – a phrase that eerily suggests the Eden from which Adam and Eve were expelled – everything was lost when his son Henry VI became king:

Whose state so many had the managing,

That they lost France, and made our England bleed.

In Henry’s journey through the play, the ambiguity exists at a personal level, as he deals with the responsibilities of his position and – notably on the eve of battle – the sin committed by his father, Henry IV, in usurping the throne. He also has to cope with the lingering memory of the waywardness of his own youth – a legend developed and explored by Shakespeare so effectively that in the public imagination it overshadows the historical realities of his early career. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely are amazed by his conversion from ‘courses vain’ and ‘companies unlettered, rude, and shallow,’ to exemplary piety and wisdom, and when Henry calls on the archbishop for an account of his claim to the French throne, the sobriety and urgency of his request spell out the grave responsibility it places on the prelate:

For God doth know how many now in health

Shall drop their blood in approbation

Of what your reverence shall incite us to.

When the king asks ‘May I with right and conscience make this claim’ the reply – ‘The sin upon my head, dreaded sovereign!’ – emphasises the consequences of such decisions for the souls of those who make them. Throughout the play, Henry’s frequent references to God both invoke His providence (‘But all this lies within the will of God, / To whom I do appeal’) and the account that must be made by kings and commoners on the Day of Judgment. The night before Agincourt, as Henry moves in disguise among his troops, he encounters a discussion among the common soldiers on this very subject: few men who die in battle ‘die well’ in the sense of having made their peace with God, and is the king responsible for the peril their eternal souls must be in? It is this argument that is fresh in his mind when, in the first of only two speeches he utters when he is alone, Henry meditates on the ‘ceremony’ that distinguishes kings from their subjects and reflects on the heavy burden placed on the monarch:

Upon the King! Let us our lives, our souls,

Our debts, our careful wives,

Our children, and our sins, lay on the King!

We must bear all. O hard condition!

But when he is summoned to the field, his next long speech – not so much a soliloquy as a prayer – is a plea that the ‘God of battles’ will not ‘think upon the fault’ that his father made in deposing Richard II. When the battle is over, and he is told the extraordinary disproportion of numbers of men lost on either side, Henry exclaims ‘O God, thy hand was here!’ and orders the singing of the ‘Non nobis’ (‘Not to us, o Lord, but to Thee let glory be given’). Any modern production of Henry V has to deal with the King’s obsession with God. A medieval setting arguably helps our understanding of this, which is probably why film and television versions of the play haven’t updated the period and why it is helpful for modern theatre audiences to view the themes of the play through the prism of a period other than our own. It certainly puts the deeply religious aspects of the play in context.

In the course of the play, Henry confronts one test after another: dealing with traitors in his court; rallying his troops at Harfleur; confronting his anxieties and the truths of warfare; fighting the battle itself; and, in the final scene, wooing a Princess who will not let him get off lightly (‘Is it possible that I should love the enemy of France?’). Meanwhile, one by one the associates of his ‘prodigal’ youth are removed from the scene: Falstaff, a surrogate father, the ‘reverend vice’ of the Henry IV plays, dies offstage; Bardolph is hanged – with Henry’s approval – for stealing from a church before the army even reaches the field of Agincourt; Nym is also executed; and Mistress Quickly, who presides over the Boar’s head tavern in Eastcheap, is reported as having died from venereal disease. Only Pistol will survive to continue a life of thieving and boasting, and to tell his version of the tale. In his mouth, it will be a false one, as he will pass off his bruises from being cudgelled as scars that he got ‘in the Gallia wars’.

In the first act the Dauphin insults the new king with a gift of tennis balls, supposedly ‘matching to his youth and vanity’. The insult from the French prince is rebuffed roundly by Henry. In one respect the Dauphin is an example of what Henry is not – restrained with difficulty by his cautious father and has little sense of strategy or decorum. In this respect, he resembles the image of the ‘wild’ prince he wrongly assumes he still has to deal with. The English king is not simply the ‘warlike Harry’ of the Chorus’s first speech, a quasi-mythical figure who assumes the demeanour (‘port’) of Mars, the god of war, with ‘famine sword and fire, / Leash’d in like hounds’ crouching at his heels. Although we have direct access to his inward thoughts only on the night before Agincourt, there is in him something of the quality of another hero who must face up to responsibilities to God and to man and to the memory of his dead father, and who is conscious of the danger to his immortal soul of the tasks he undertakes – his near contemporary, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.

Russell Jackson is Allardyce Nicoll Professor of Drama at the University of Birmingham. His most recent publications include Shakespeare Films in the Making (2007) and Theatres on Film: How the Cinema Imagines the Stage (2013).

King Henry V (Jude Law)

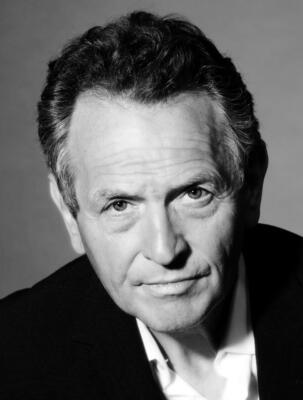

Duke of Exeter (James Laurenson)

Uncle to King Henry

Earl of Westmoreland (Edward Harrison)

Archbishop of Canterbury (Michael Hadley)

Bishop of Ely & Charles VI (Richard Clifford)

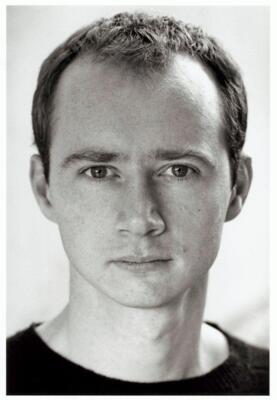

Lord Scroop & Lewis – The Dauphin (Ben Lloyd-Hughes)

Sir Thomas Grey and Gower (Harry Atwell)

Gower – Officer in King Henry’s army

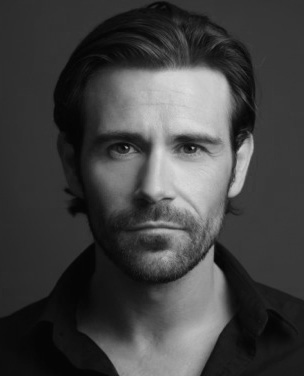

Fluellen (Matt Ryan)

Officer in King Henry’s army

Macmorris (Christopher Heyward)

Officer in King Henry’s army

Bates & Bardolph (Jason Baughan)

Bates – Officer in King Henry’s army

Williams & Nym (Norman Bowman)

Williams – Officer in King Henry’s army

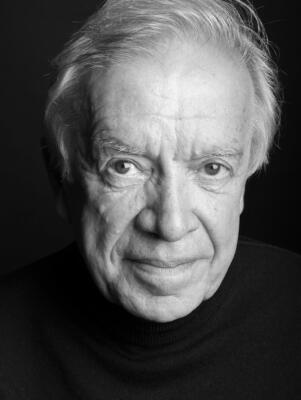

Pistol (Ron Cook)

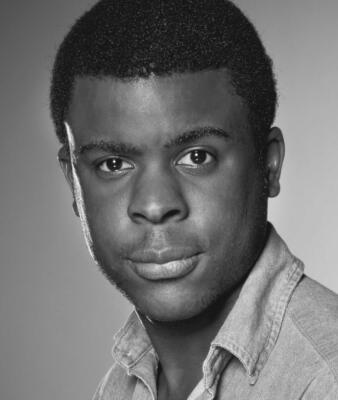

Boy/Chorus (Ashley Zhangazha)

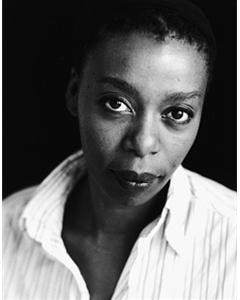

Mistress Quickly & Alice (Noma Dumezweni)

Duke of Orleans (Christopher Heyward)

The Constable of France (Ian Drysdale)

Montjoy (Prasanna Puwanarajah)

Governor of Harfleur (Rhys Meredith)

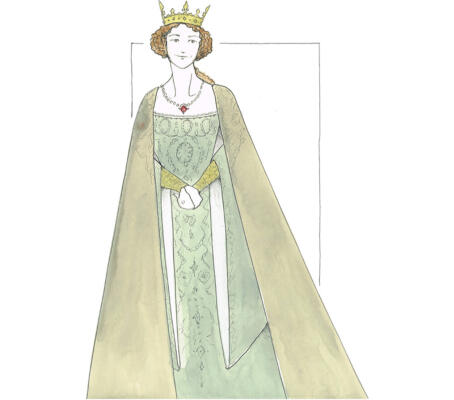

Katherine (Jessie Buckley)

Ensemble (Fred Lancaster)

Lords, Ladies, Officers, French and English Soldiers, Citizens, Messengers and Attendants

Ensemble (Maddie Rice)

Lords, Ladies, Officers, French and English Soldiers, Citizens, Messengers and Attendants

Henry V by William Shakespeare (Michael Grandage Company, Ltd., 2013). The text of MGC’s 2013 production of the play at the Noel Coward Theatre. Many other editions, with introductions and commentaries, are available.

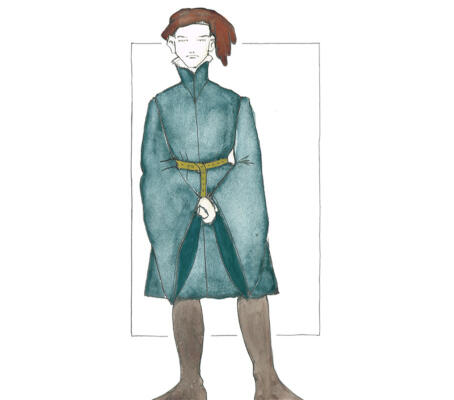

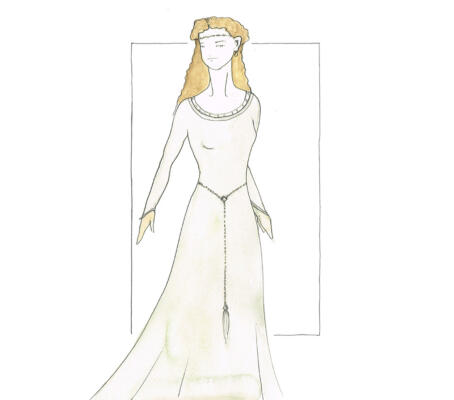

The following books were in the rehearsal room for Henry V:

- Agincourt 1415 – Matthew Bennet (Osprey, 1991)

- Medieval Design (Pepin Press)

- Medieval Costume and Fashion – Herbert Norris (Dover, 1999)

- Western European Costume – Thirteenth to Seventeenth Century – Volume One – Iris Brooke (George Harrap, 1939)

- Medieval Costume in England and France – The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries – Mary G. Houston (Dover, 1939)

- English Costume of the Later Middle Ages –The Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries – Iris Brooke (A&C Black, 1935)

- The History and Meaning of Heraldry – Stephen Slater (Southwater, 2003)