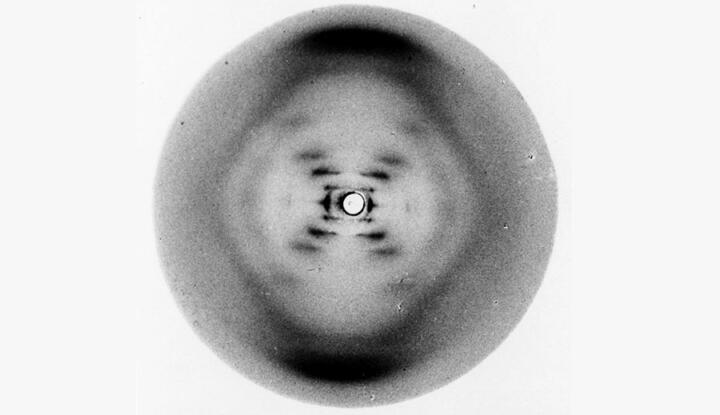

Photograph 51

“The instant I saw the photograph my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race.”

About the work

2015

Welcome to the Michael Grandage Company’s production of Photograph 51 by Anna Ziegler

Does Rosalind Franklin know how precious her photograph is? In the race to unlock the secret of life it could be the one to hold the key. With rival scientists looking everywhere for the answer, who will be first to see it and, more importantly, understand it?

Anna Ziegler’s extraordinary play looks at the woman who cracked DNA and asks what is sacrificed in the pursuit of science, love and a place in history.

“I read Photograph 51 and liked it instantly. Theatrically, it was constructed rather like a thriller. It’s a true and terrible story of injustice, in which this woman scientist, Rosalind Franklin, who was operating entirely in a man’s world, found herself competing in a race to discover “the secret of life”.

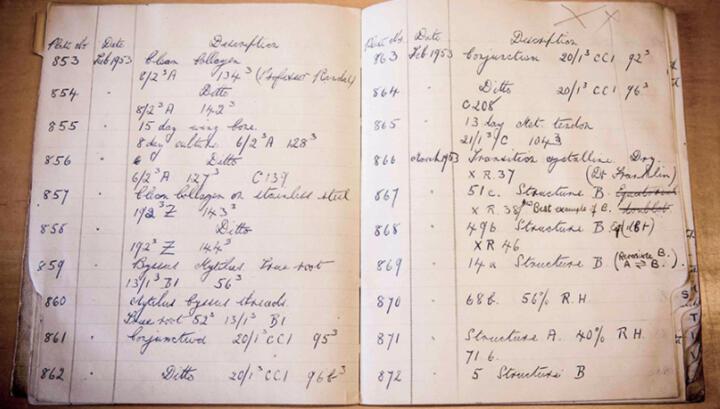

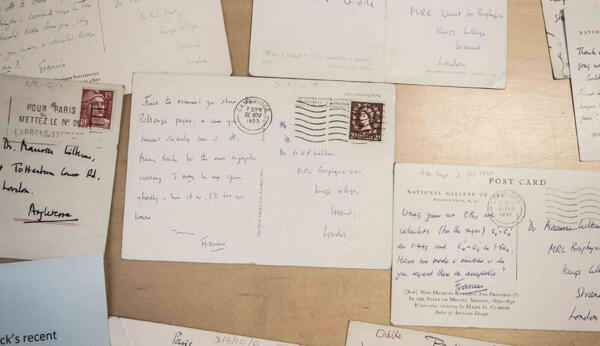

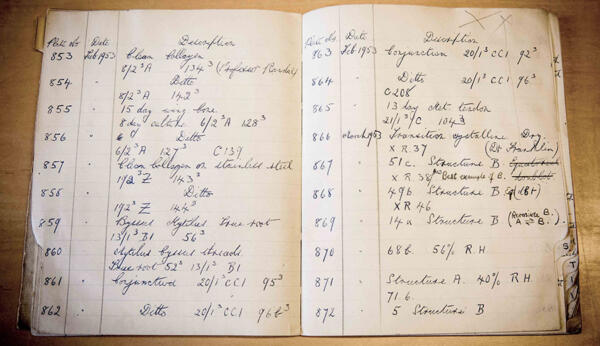

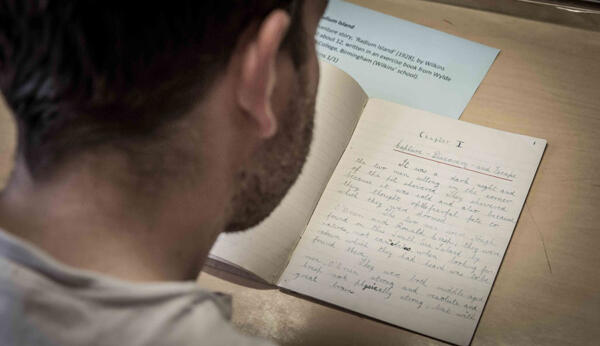

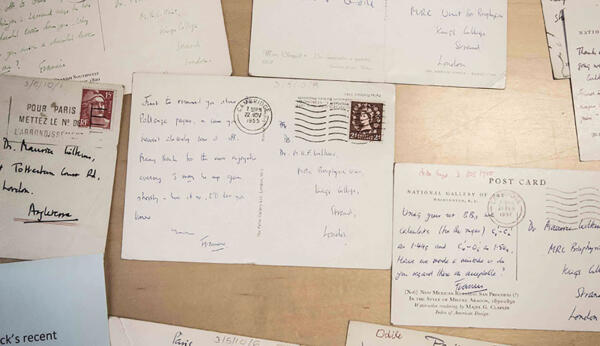

Nobody knew how DNA was constructed and she took a series of X-ray photographs, of which number 51 was the clearest, and it enabled scientists to see how the structure of DNA worked for the first time. The photograph she took showed DNA to be made up of a double helix and it enabled two scientists in particular, Francis Crick and James Watson, to build a model based on that information. Both men went on to win the Nobel Prize.

Rosalind Franklin died young but her research and her photographs are now believed to have played a significant part in the discovery. It’s thrilling to tell her story on stage for the first time.”

Michael Grandage, Artistic Director, MGC

England, 1951.

After the devastation of World War II, amidst the rubble of cleared bombsites, scientists at the country’s leading universities attempt to discover the building blocks of life itself: DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid). At King’s College in London, a determined and dedicated doctor specialising in X-Ray Crystallography – Rosalind Franklin – has just joined the staff, working closely with Maurice Wilkins.

But it is a difficult relationship from the start. Rosalind, a serious-minded and independent professional, finds the reserved and rather pompous Maurice infuriating, particularly in his reluctance to recognise her credentials. He, in turn, finds her forthright manner combative, only exacerbating his natural awkwardness around women. The pair struggle to forge an alliance and share their findings, with Rosalind feeling increasingly isolated – a lone woman in a man’s world.

Meanwhile at Cambridge University, Maurice’s old university friend and fellow scientist, Francis Crick, has teamed up with an ambitious and brash young doctor, James Watson. Together they have joined the race to unlock the secret of life, but they can’t do it alone… They need Rosalind’s expertise, as demonstrated in her photographs, to prove their hypothesis.

Who will find and recognise the vital piece of evidence needed to win the race? And at what price, both professional and personal, will victory come?

| Role | Credit |

|---|---|

| Director | Michael Grandage |

| Set & Costume Designer | Christopher Oram |

| Lighting Designer | Neil Austin |

| Composer & Sound Designer | Adam Cork |

| Casting Director | Anne McNulty CDG |

| Wig & Hair Designer | Christine Blundell |

| Production Manager | Patrick Molony |

| Associate Production Manager | Kate West |

| Company Stage Manager | Howard Jepson |

| Deputy Stage Manager | Sharon Hobden |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Georgia Bird |

| Dialect Coach to Ms Kidman | Sandra Frieze |

| Voice Coach | Zabarjad Salam |

| Props Supervisor | Celia Strainge |

| Costume Supervisor | Anna Josephs |

| Head of Wardrobe | Charlotte Stidwell |

| Head of Wigs & Make-Up | Sophie Finch |

| Deputy Head of Wardrobe | Amanda Wilde |

| Associate Director | John Haidar |

| Associate Set & Costume Designer | Lee Newby |

Anna Ziegler

Anna Ziegler’s plays include The Last Match (upcoming at The Old Globe Theatre in San Diego, CA and City Theatre in Pittsburgh, PA), Boy (upcoming at Keen Company/Ensemble Studio Theatre in New York City), A Delicate Ship (The Playwrights Realm, August-September, 2015 at the Peter Jay Sharp Theater, New York City/Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park), Another Way Home (upcoming in Washington DC at Theater J; Magic Theatre, San Francisco, CA), Dov and Ali (Theatre503; The Playwrights Realm), The Minotaur (Rorschach Theatre; Synchronicity Theatre) and BFF (WET Productions at the DR2 Theatre, New York City).

She has been commissioned by The Manhattan Theatre Club, Seattle Repertory Theatre, Ensemble Studio Theatre, Virginia Stage Company and New Georges. Her plays have been developed at The Sundance Theatre Lab, The O’Neill National Playwrights Conference, The Williamstown Theatre Festival, New York Stage and Film, The Araca Group, Old Vic New Voices and Soho Rep’s Writer/Director Lab, among others.

Anna is a graduate of Yale College and holds an MA in Dramatic Writing from the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University.

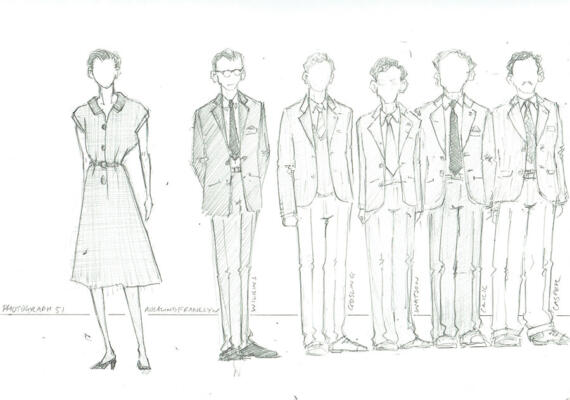

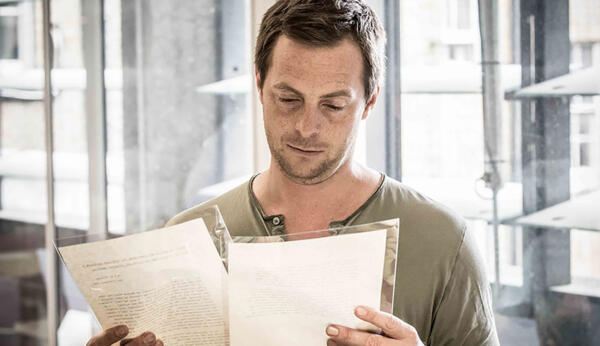

Maurice Wilkins (Stephen Campbell Moore)

A scientist in his 30s or 40s

“White, British, formal and polite, Rosalind’s sparring partner and equal, a wounded, gentle soul but not bumbling or buffoonish. Bewildered when his cluelessly patronising attempts at kindness towards Rosalind are rebuffed. A man who’s had trouble understanding women all his life. A little haughty when it comes to intellectual matters, and the opposite around matters of the heart (but a certain level of decorum stops him from examining this even on his own).”

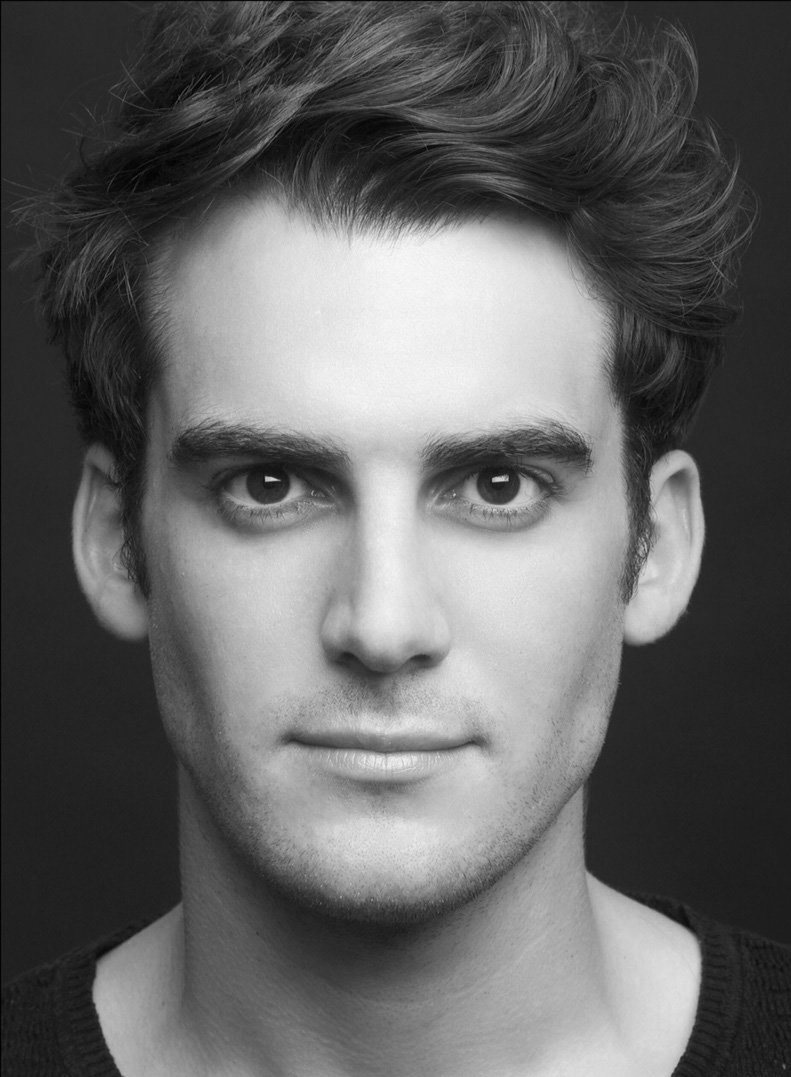

James Watson (Will Attenborough)

A scientist in his early 20s

“White, American, all confidence, arrogance, most of all hunger and drive. He is not without humour but is blunt and sharp-tongued. When he is sure of something he will stop at nothing to get it, and he has a very wide-ranging moral code (or lacks one entirely). He’s a genius and knows it. But he’s odd and nerdy too – he would not easily pick up a woman in a pub – a sore subject and perhaps what he needs to make up for with scientific excellence.”

Francis Crick (Edward Bennett)

A scientist in his 30s or 40s

“White, British, very proper, not unkind, brash, good with the ladies, a philosopher, likes to be the centre of attention, cracking jokes. A ringmaster. He is not as openly driven as Watson but also has a greater need for success. He’s been at it longer and knows what it is to feel one is failing at one’s life pursuit. He and Watson have terrific chemistry; they enjoy each other immensely.”

Don Caspar (Patrick Kennedy)

A scientist in his 20s or 30s

“White, Jewish, American, open and affable, honest, incredibly smart but humble. A touch naïve, perhaps – it would not occur to him that merit wouldn’t be rewarded. A graduate student with a true wonder about the world, who wears his heart and soul on his sleeve.”

Ray Gosling (Joshua Silver)

A scientist in his 20s

“White, British, awkward, endearing, sweet. A graduate student who lacks self‑confidence and is always stuck in the middle of two feuding mentors.”